- K

- K

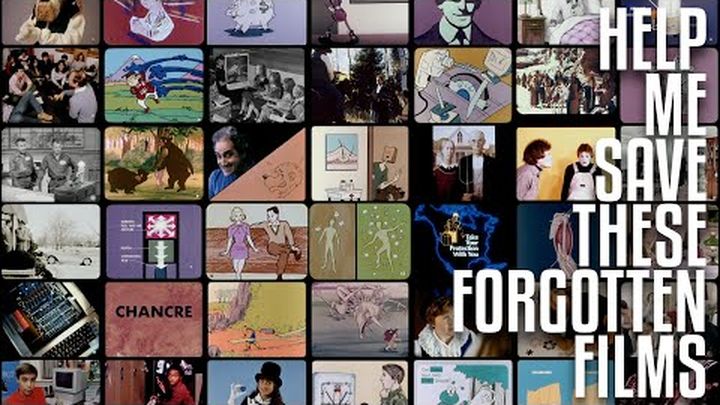

As far as I can tell, I'm the only person actively preserving American educational filmstrips, a forgotten 20th-century multimedia format used in classrooms, industry, and corporate training from the 1920s through the 1990s. My work was recognized in the Internet Archive's 2024 Vanishing Culture Report.

These projected still-image presentations were everywhere: science classes, history lessons, sex education, civil defense drills, corporate sales training, service departments at Ford and Chrysler. Millions were produced. Today, most have been thrown away, and many that survive are actively decomposing on Eastmancolor stock that's faded to a deep red. Others sit in eBay listings priced as vintage décor by sellers who don't realize they may be holding the last surviving copy of something historically significant.

Because many filmstrips also came with an audio soundtrack on record or cassette meant to be played in sync with the film, many of those soundtracks have been separated from the filmstrips due to negligence or ignorance. When a filmstrip is missing its soundtrack or vice-versa, it's missing part of the original presentation, and can't be restored.

I've preserved over 1,300 filmstrips so far, all freely available on the Internet Archive. But I have more than 3,000 waiting—and people keep donating more as they learn about this work.

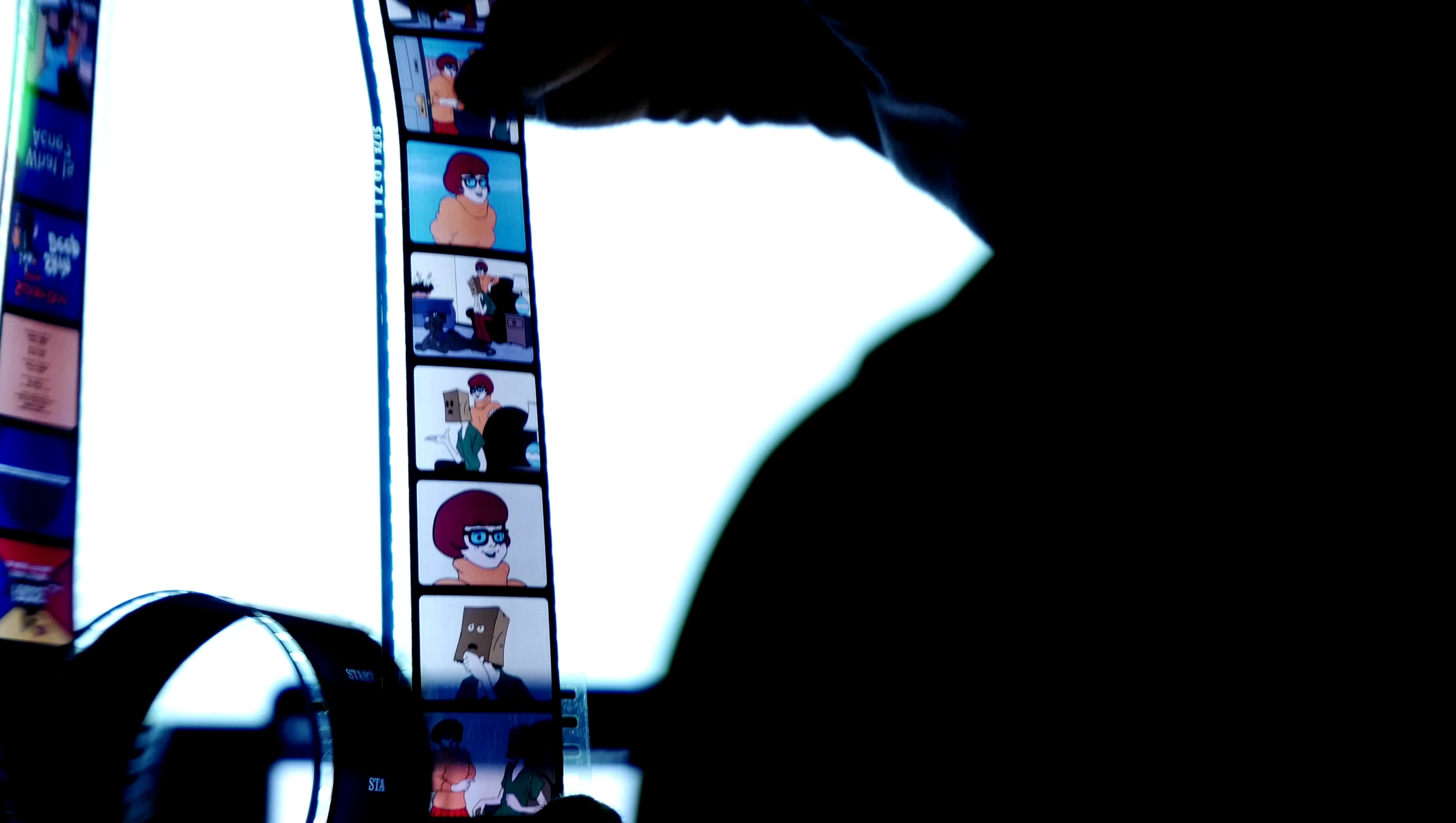

Preserving filmstrips is painstaking and time-consuming. Consumer-grade tools don't exist for this format, so I have to scan each frame individually on a flatbed scanner. This can take up to three minutes per frame, with some filmstrips exceeding 100 frames. And because only a certain number of frames can fit on a flatbed scanner, it's not like I can load a filmstrip with 150 frames and walk away for the rest of the day; I have to be here to reload it about once an hour.

If I'm lucky enough to have a filmstrip and its soundtrack, I can restore the filmstrip into a video resembling how it would have been viewed decades ago.

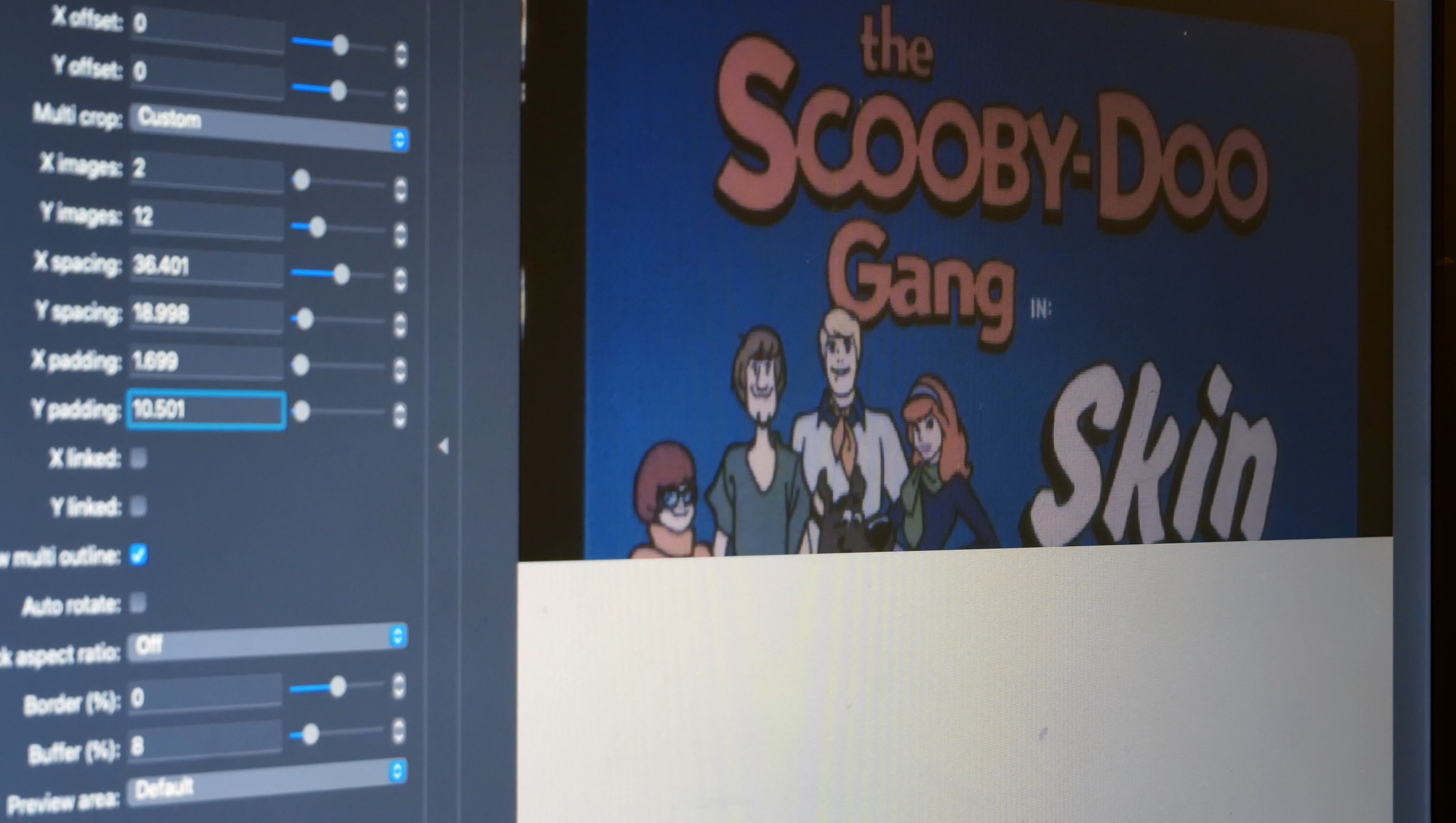

The restoration process is multi-disciplinary, with some steps only being necessary because professional film scanners are out of reach. Because flatbed scanners have no film gate or sprocket drive like real film scanners, each frame needs to be manually cropped and deskewed, a process which takes another three or four minutes per frame. Despite the promise of AI and machine learning, there is no automated tool that does this correctly, and no human has been able to create one for me either. In addition, restoring a filmstrip involves digitizing its soundtrack from cassette or record, correcting faded colors when possible, and assembling everything in a video editor, making sure it has that proper old-school feel of a student standing at the projector advancing frames when she hears the beep.

In 2025, I held the first-ever Filmstrip Festival, a three-day online showcase of restored filmstrips with commentary and a look behind the scenes. I also host a weekly show called Is This Anything? searching for endangered or lost media on donated VHS tapes. And every two weeks, I release a newly restored filmstrip to my growing audience.

But despite all this, financial support dropped low enough last year that I had to take a job driving for DoorDash to keep our bills paid, fitting in preservation work late at night or in a parking lot between orders on my laptop. Fewer films got saved as a result. I'm not asking for much, just enough to focus on this work full-time instead of splitting my energy between saving rare films and delivering takeout (for less money than I'm actually spending in gas and future car repairs).

Your support keeps this work alive. It covers my time, equipment, storage, and basic expenses so I can focus on preservation instead of side work. Exceeding this goal could fund better scanning equipment to dramatically speed up the process. Right now, my tools are the bottleneck.

I hope you can help me save this endangered format before it's too late.