- B

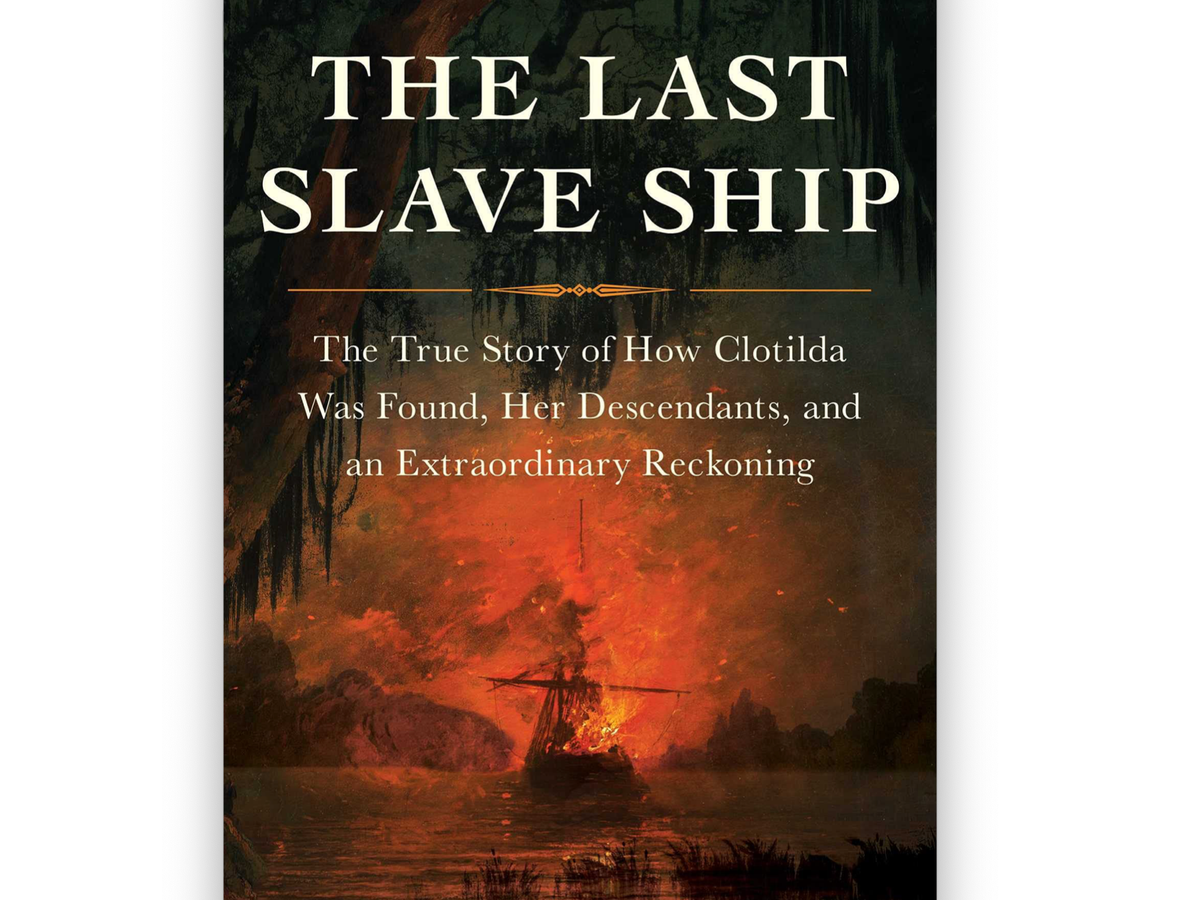

My name is Ben Raines. I found the wreck of the Clotilda, the last ship to bring enslaved Africans to the United States. I am raising money to put my new book, The Last Slave Ship - The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning, into the hands of every student in the schools around Africatown, Alabama - the town founded by the Africans who were smuggled into the country in the hold of the Clotilda. The book comes out Jan. 25, so I'm trying to raise the money quickly so the kids get the books the day it is officially published. Here's a link to the Amazon page for the book:

Africatown is the only community in America founded by enslaved Africans, and many of their descendants still live there today. In fact, one of the schools I hope to provide books for was originally started by the Africans around 1880 -- one of the first schools for African Americans in the South. But Africatown is a shadow of what it once was, with a tenth of the population it had as recently as the 1980s. Decades of systemic racism at the city and state level have destroyed the town's commercial district, wiped out thousands of homes, and surrounded the community with some of the most polluting industries on Earth.

Sadly, much of Africatown's incredible and rich history is unknown to many of the people living there today. That's why making sure as many copies of the book end up in Africatown as possible is important to me. I'm trying to raise enough money to buy 1,800 books, which would provide a book to every student at the original middle school in Africatown and at the two high schools that kids from Africatown attend. All money raised by this effort will go toward books for schools. If we raise more money, we'll put books in more places. This generation will be the keepers of the Clotilda story going forward. They deserve a chance to grow up knowing the full and triumphant story of the people who founded their town, to know who their ancestors were.

In broad strokes, the story of the Clotilda involves an Alabama steamboat captain and plantation owner who made a bet that he could import a cargo of Africans, even though it had been illegal to import enslaved people for more than 50 years. The captain was successful, and delivered 110 people from Benin in West Africa to Mobile, Alabama in 1860. When the Civil War ended five years later, the Africans were suddenly free, but trapped thousands of miles from home on the opposite side of the world. Showing incredible strength, the Africans banded together, saved up their money, and bought land from the men who had enslaved them, creating a new life in America.

One of the the most unique things about the story of the Clotilda and its passengers is how well documented everything is, from the captain’s journal chronicling the voyage and purchase of the captives, to interviews the freed captives gave later in life. The Africans were young, most 20 or under, when they were captured in 1860, many of them lived into the 20th century, which meant they were interviewed dozens of times by journalists and historians. Because of this, we know more about the people who arrived in the Clotilda’s hold than is known about any of the millions of people who were enslaved in the Americas. We know exactly what part of Africa they came from, what their lives were like there, who captured and sold them, who bought them, exactly when they arrived in America, and what happened to them once they were here. We know the horrors of an African slaving raid from their experience, and we know how desperately they longed for home and the loved ones they knew had either been killed or captured and enslaved. In a way, the Clotilda and the story of its passengers serves as a sort of proxy for what happened to everyone who stolen from Africa. The well-documented experience of the Clotilda captives illuminates and informs the lost histories of millions of African-American families who know only that their forebears were also stolen and shipped across the ocean.

Africatown’s history was one of ascent, from the moment the Clotilda’s captives pooled their money and bought land from their former enslavers after Emancipation. I believe the Clotilda's passengers were the first group in the nation to ask for reparations. While they were unsuccessful, it was a bold thing to demand land from your enslaver within weeks of being freed. The group -- many of whom had been captured in the same town during a devastatingly brutal slaving raid in what is now modern day Benin -- took turns building each other’s houses and creating community buildings. In her book Barracoon, Zora Neale Hurston quotes Clotilda passenger Cudjo Lewis saying the group set out to create “an African Town” where they could govern themselves according to the tribal customs they had grown up with. By the 1880s, they had added the area’s first church and a school for their children, one of the first in the south for African Americans. As Cudjo explained to Hurston, “We Afficky men doan wait lak de other colored people till de white folks gittee ready to build us a school. We build one for ourself.”

Cudjo Lewis:

That self-reliant attitude allowed the Clotilda’s captives to thrive in the Jim Crow South. By 1921, Africatown was the fourth largest community in the country governed by Blacks, and the only one started by people born in Africa. When Cudjo, the last of the original settlers, died in 1935, Africatown was known as an idyllic place, with a mild climate and plentiful jobs at nearby factories. By the 1960s, the population had swelled to 12,000 and two kids who grew up playing baseball for the original Africatown school were on the 1968 “Miracle Mets” team that won the World Series. Then things began to fall apart.

Africatown, listed on the National Registry of Historic Places, has experienced a devastating decline in recent decades. The community was knocked from its perch as one of the most successful African American communities in the nation primarily by the intentional actions of city and state leaders in Alabama, one of the nation’s most notoriously racist states. In the 1950s, the community had grocery stores, restaurants, barber shops, dry cleaners, a movie theater. Today, there are no businesses in Africatown – not even a gas station, a Circle K, or a drugstore. Nothing. The population has dwindled to 2,000. The main culprit in the decline was a decision to build a massive 5 lane highway through the center of town in 1992, which split neighborhoods in half, and obliterated the commercial district.

Huge swaths of the original properties purchased by the Africans from their enslavers were confiscated through eminent domain. Descendants of the original settlers had lived on those properties for a century, in houses built by the newly freed Africans. Cudjo Lewis’s one room cabin, where he was interviewed by Hurston, was among the many homes destroyed to build the road. A small brick chimney next to the highway is the only thing still standing in Africatown that was built by the settlers.

There is an ongoing effort to try to restore Africatown, and the discovery of the Clotilda is a part of that. Residents hope that the ship will be dug up from the swamp where I found it and put on display in a new museum. This is me holding the first piece of the Clotilda to see the light of day in 160 years:

The hope is that the museum, in turn, will help restore some of what has been lost in Africatown. That's why it is so important to share Africatown's history with the people who live there, for the most important thing they've lost is the very story of their ancestors.

The book has received exceptional reviews so far, with Publishers Weekly calling it "An evocative and informative tale of exploitation, deceit, and resilience,” and the Kirkus Review recognizing it as a "book of extraordinary merit." Dr. Joshua Rothman, head of the history department at the University of Alabama had this to say: "The Last Slave Ship is all at once the true story of a terrible crime and its survivors, a riveting account of discovering the evidence its perpetrators hoped would never be found, and a moving attempt to grapple with its legacy. We may never ultimately be able to reckon adequately with slavery, but Ben Raines reminds us that the task’s immensity is no excuse for neglecting it. This is a powerful and important book."

Help me put copies of the book where it matters most: in the hands of the children of Africatown.