Help Me Write Book About My Struggle With Autism & C-PTSD

Donation protected

Help Me Write A Book About My Long Struggle With Undiagnosed Autism & C-PTSD

Summary & Request for Your Help

My name is Paddy Docherty and a few years ago my life fell apart when my social impact business in Africa collapsed after a long and desperate effort to keep it going, leading me into bankruptcy and a precarious living situation fraught with mental health struggles. At the same time, I was finally diagnosed with autism, a condition that explains a great deal about my difficulties and unsettled life over the decades. It has recently emerged that I am also suffering from C-PTSD (complex post-traumatic stress disorder) as a result of the sustained and extreme stresses of trying to keep the business afloat over several years.

I now want to ask for your support in my plan to get myself back on track by writing a book about my experience. I don’t mind that I lost everything when the business collapsed (that was the risk that I took in setting up the company) but unfortunately my C-PTSD went unrecognised (and thus untreated) for so long that it deteriorated to the point where I cannot presently work in a normal job: I urgently need respite and treatment, but I want to be productive at the same time.

This request for assistance is therefore designed to give me time and a little tranquility to focus on recovery and therapy, while writing a book aimed at contributing to the discussion of issues that are still very often seen – sadly – as too shameful to be mentioned. The requested funds will pay for nine months of basic living costs in a small cabin in the middle of nowhere in Wales, as well as a weekly therapy session online. This will be very frugal living, but for me right now the greatest luxury is peace and quiet, so basic living is no problem at all!

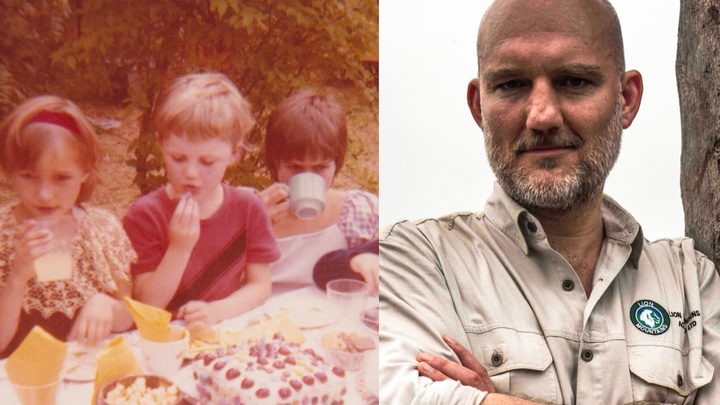

Undiagnosed autism (as well as other types of neurodivergence) and unaddressed mental health issues cause many thousands of people to suffer in silence. Men especially face enormous social pressures to deny their problems, and this can seriously damage ourselves and those around us. We need to be more open about it and I want to contribute to that by sharing my story. Even strapping big lads suffer from mental health issues, and we should talk about it more openly…

Please consider supporting me in this task by making a donation. This would transform my life and future, and help me make a difference to the lives of others too.

Detailed Background [Optional Reading]

Early life & adventures

I had an eccentric upbringing (hippy artist parents) in a tumbledown house in the middle of a wood in the Gloucestershire countryside – a house that felt like it was literally held up by the great piles of books inside.

It was strange, creative, and in many ways idyllic, such that we didn’t understand that we were a bit odd (and very poor). Success at school (prizes, scholarship for a prestigious private school, etc) also masked some of the weirdness, and this gives me the title of my memoir: LITTLE BOY FROM THE WOODS.

This was what my terribly sweet grandmother would say on her visits down from Scotland, when presented with new evidence of some educational achievement: “not bad for a little boy from the woods!”… At the time, I remember bridling internally at the characterisation (“I’m not little, I’m big and strong!”) but looking back, it nicely captures something of the reality, even as I started reading Nietzsche as a teenager and becoming deeply (but confusedly) dissatisfied at our family economic situation.

In brief, after boarding school and Oxford University (where I won a Blue for boxing and was Junior Dean at Brasenose College), I entered upon a varied career that included some of what are usually taken as the markers of success. On the face of it, all probably seemed well to outside observers, but with hindsight now enabled by my autism diagnosis, I can see the disruptive pattern of my unsettled career progress and how (unbeknownst to me at the time) it reflects the difficulties of living with unrecognised neurodivergence.

This meant that while I joined some prestigious companies (including PricewaterhouseCoopers), I would also often swiftly leave those excellent jobs for reasons that seemed inexplicable to family and friends (my apologies to Stefka…), as if driven by hidden and little-understood impulses.

Over the years, I lived on a cattle ranch in South Africa, worked in oil & gas corporate finance, had an internet startup, was briefly a shipbroker then an investment banker, accidentally lived in Bahrain for six months, was in a shooting in Lagos, Nigeria (my boss took two bullets, but don’t worry, he survived), and was arrested as a spy in East Africa. I travelled in Pakistan and Afghanistan and wrote a book published by Faber & Faber (THE KHYBER PASS , 2007) and then lived in Prague for a year. I have always been keen to cram in adventures and incident, to make life as interesting as possible, but my autism diagnosis makes me see this erratic life in a new light.

My African Project

Through this mixture of creative ambitions and neurodivergent impulses, I finally came to establish Phoenix Africa, a company aimed at harnessing private investment for building peace and security in post-conflict countries in Africa. For the best part of a decade, I worked extremely hard to raise finance for building a series of social impact agriculture operations, principally our first project, Lion Mountains Agrico Ltd, a rice farming & distribution business in Sierra Leone.

Battling against investor disinterest and the Ebola outbreak, we employed a few dozen local people and developed a network of several thousand outgrower farmers, from whom we would buy rice for milling and sale in our network of kiosks around Bo District. Lion Mountains was for a time the No 1 rice operation in Sierra Leone – our mission was to free Sierra Leone from its absurd reliance on rice imports, while contributing to the creation of peace and security in a country not long out of civil war. You can read something about the project in The Independent, both here and here.

Crisis

Sadly, however, I was ultimately unable to raise the millions of dollars that the company needed to keep going. Not many investors will bother to take an interest in post-conflict Africa, and especially in a project with a social impact mission. Eventually our main investor (who had challenges of his own) had to pull out. Having tried everything (and having sold whatever of value I myself had in order to pay the monthly salary bill for as long as I could), the business finally went under in 2018 and I was forced into personal bankruptcy as well. It was at this time that I received my autism diagnosis after a very lengthy process, and began a precarious period of relying on family support and whatever ad hoc temporary/remote work that I could find, while struggling with the mental health problems that accompany autistic burnout (depression, anxiety, alexithymia, extreme sensory sensitivity, etc).

Through this period I was doing my best to be productive, and while living with these symptoms I have managed to publish a book – BLOOD AND BRONZE – with Hurst & Co, as well as complete my PhD. The key factor is that these are things that can be done while I’m locked away in solitude, alone in a quiet room with books and ear defenders. I am determined to achieve self-sufficiency, I just cannot at the moment function in a normal workplace, so my options for making a living are currently very limited. I had recently wangled an offer of a university post in India, in the foothills of the Himalayas, thinking that it would provide the peace and quiet that I desperately need, but sadly that fell through.

Moreover, it is only in the last few weeks that it has become evident that I am also struggling with C-PTSD and have been for over a decade. For all this time, I had just thought that *this* is what it’s like to be autistic, and was grinding on as best as I could. Paradoxically, however, this realisation is cause for hope: the symptoms of C-PTSD can be treated. That has come as a revelation to me: there is in fact a prospect that I can recover, at least sufficient to live somewhat more normally and to be able to support myself. I’m delighted to say that I have just begun therapy online.

My plan

With your support, I will now get out of my present difficulties by writing LITTLE BOY FROM THE WOODS. A good friend has arranged a low-cost cabin in the middle of nowhere in Wales, and all funds raised here will go towards paying for nine months of basic living costs while I write the book and complete therapy in this quiet refuge. Your generous assistance will allow me to break out of my current impasse, sort out my C-PTSD symptoms, and set me up for a self-sufficient future of writing, mental health advocacy, and talking about neurodiversity.

I can absolutely promise that I will complete this project: I have already published two books, and I have my agent standing by to take the manuscript to publishers when ready. I have no doubt about my capacity to do this, given the necessary peace and quiet for a few months; I would be incredibly grateful for all the support that you can offer.

Additional incentives

As some tiny additional incentives for supporters, I can promise that:

• The first ten AND the biggest ten donors will get a mention in the Acknowledgments section when the book is finally published

• All donors will be entered into a prize draw upon publication, for five signed copies to be sent anywhere in the world

The book and my new mission

From the above, it will be clear that my story, and the story of the book, is therefore that of a little boy from the woods trying (and trying too hard) to be successful in a world that didn’t really make sense to his overly sensitive autistic brain. I now understand that much of the challenge that I faced was due to my high level of masking, as an undiagnosed autistic in a neurotypical world: for someone with autism (also still known to some by the contested term Asperger’s), masking comes at a significant psychic cost and is exceptionally draining. The National Autistic Society reports that possibly as many as 45% of autistic people live with PTSD.

This is also a story of the way in which a person with some significant advantages/privileges (in the world as currently organised) can also be struggling, even living in a state of near-collapse, with mental health problems and challenges arising from being neurodivergent in a society arranged for neurotypicals. Despite the greater public willingness to recognise mental health issues and the existence of neurodiversity in recent years, we still don’t talk about it enough: this is what I now want to help address. By sharing the story of my own struggles with undiagnosed autism and untreated C-PTSD, I hope that I can contribute to normalising discussion of issues that are still often regarded as too shameful to admit.

Many thanks for your consideration of this appeal. I hope that together we can make LITTLE BOY FROM THE WOODS a reality.

Organizer

Paddy Docherty

Organizer

England