Support war sailor Oscar Anderson (102)

STØTT 102 ÅR GAMLE OSCAR!

(English text below)

Jeg heter Roger Albrigtsen, jeg er forfatter og samler inn penger til en av våre siste krigsseilere som bor i England, saken om 102 år gamle Oscar Anderson er kjent fra NRK og Fri Fagbevegelse.

Denne innsamlingen er til Oscar, alle midlene som kommer inn går direkte til han for å dekke kostnadene for sykehjemsoppholdet samt å støtte ekteparet i en vanskelig tid.

Forfatter Roger Albrigtsen var i oktober 2023 en uke i England og sammen med pensjonert sjøkaptein Wiktor Mølleskog fikk han besøkt Oscar og kona ved flere anledninger.

I slutten av januar 2024 reiser Albrigtsen nok en tur på besøk til Oscar. Oppdateringer fra besøket vil legges ut i innsamlingen.

NAV har avslått å refundere ekteparets utlegg som i perioden mai til september 2023 beløp seg til rundt kr. 300 000,- Oscars kone har solgt smykkene hennes for å betale for sykehjemsplassen.

https://frifagbevegelse.no/nyheter/frp-krever-at-regjeringen-snur-og-hjelper-krigsseilere-som-oscar-102-6.158.1019595.998befacc5

https://frifagbevegelse.no/maritim-logg/na-slipper-krigsseileren-oscar-102-a-flytte-i-campingvogn-6.158.1019171.0536234c07

Takk til alle som bidrar fra hjertet! Takk!

Har du spørsmål om innsamlingen kontakt Roger Albrigtsen via melding på denne siden.

Support Oscar!

Norwegian war sailor in Britain may end up living in a caravan. A 102 year old WW2 hero.

Hi, my name is Roger Albrigtsen. I am an author fundraising for one of the last Norwegian merchant warsailors of WW2 living in Great Britain. Helping me ro raise money is Wiktor Mølleskog living in London.

This fundraiser is from our hearts and all the funds go to Oscar.

More info below/mer informasjon finner du lengre ned.

Wiktor Mølleskog and Oscar. Photo by Roger Albrigtsen

………….

UPDATE OCTOBER 8.

Photos from the visit added

Oscar meeting a four month old puppy at the nursing home. Photo by Roger Albrigtsen

Roger Albrigtsen and Oscar Anderson. Photo by Wiktor Mølleskog

UPDATE:

Tania Michelet, daughter of Norwegian novelist Jon Michelet, on war sailors:

The War Sailors - Norway’s Fallen Merchant Sailors

The sacrifices made by war sailors during the Second World War are considered to be Norway's most important contribution to the Allied victory over the German military power.

Under extremely difficult conditions, Norwegian merchant ships transported fuel, war supplies, and other goods, primarily across the Atlantic Ocean but also in the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, and the western part of the Pacific Ocean - important supply lines that eventually became convoy routes in the Atlantic. These routes ran from New York and Halifax to Liverpool, from Sierra Leone to Port of Spain or Liverpool, from Gibraltar to New York or Liverpool, and from Liverpool to Murmansk (the Murmansk convoys).

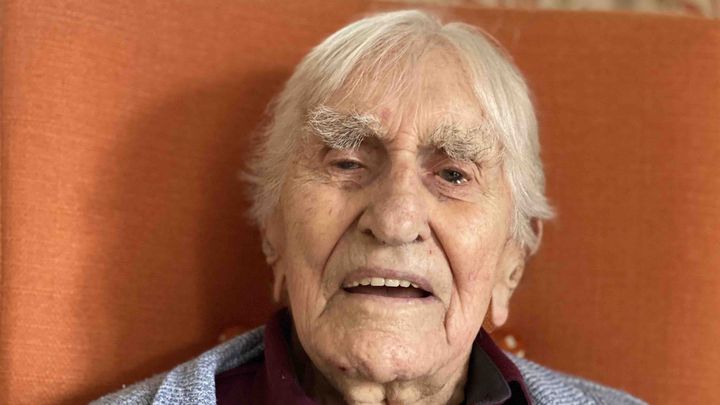

Oscar Anderson (102). Photo by Roger Albrigtsen

Besides those who were on board ships outside Norway (the outer fleet), there were also many war sailors in Norwegian and Nordic waters (the home fleet). Ships in the outer fleet sailed to Allied ports when Norway was occupied in April 1940, and ships that were in Norwegian and Nordic-occupied waters, including passenger ships such as the Hurtigruten and those travelling the coastal routes, were put under German control.

During the war years, seamen who sailed abroad were a particularly vulnerable group. They experienced considerable psychological stress and were under constant threat of violent death; helpless and defenseless in the face of superior forces and enemy air and submarine attacks. They also suffered because of the lack of connection with family and friends back home in Norway.

With no landmass connecting the three great war allies, as they were then, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States; all of the weapons, fuel, food, and other equipment made necessary by war had to be transported by sea. Norway was the world's fourth-largest shipping nation at the time, and when the country was occupied seven months after the outbreak of war in 1939, it became extremely important for the belligerents to secure control over Norwegian ships sailing in global waters.

Oscar and Wiktor Mølleskog. Photo by Roger Albrigtsen

Thanks to the Norwegian captains who refused to be enticed by the Nazis to sail home to an occupied Norway, most of the Norwegian merchant fleet came under Allied control, and because the Norwegian government-in-exile in London had requisitioned all ships into one joint state shipping company (Nortraship), they could continue to sail under the Norwegian flag and earn money for the Norwegian state. This strengthened the London government politically and economically and also ensured an efficient and vital means of transport for the Allies.

Letter to Oscar after meeting schoolchildren. From private collection

The importance of the sailors' efforts can, in many ways, be measured by how much the German military invested to stop this transport. Most feared were the hundreds of submarines that were sent out into the seas either in groups or alone. Bombers were also deployed, mines were laid, and warships were sent out into the oceans to hijack or sink Allied shipping. This had fatal consequences for the sailors.

Letter to Oscar after meeting schoolchildren. From private collection

In the 4th volume of my father Jon Michelet's six-volume work, "A Hero of the Sea, Bloody Beaches”, we meet the main character, Halvor Skramstad (nicknamed Skogsmatrosen or Forest Seaman because he comes from the forests of Hedmark), after he has been torpedoed in Florida Bay:

'As long as the ship sails’ is sung by the crew:

"As long as the ship can sail, as long as the heart can beat, as long as the sun glitters blue on the waves, if only for a day or two, then be thankful anyway, because there are many who will never get a glimpse of light!"

Halvor travels and experiences the horrors of war, and we are with him. Out on the blue waves, always free, as long as the ship can go on!

After a ship was torpedoed. Photo from Roger Albrigtens archive

Dad was struck down by illness, and on his deathbed he struggled to write his last book in the series, fittingly entitled "The Warrior's Homecoming." It was difficult for him to finish the book before he died, particularly as it deals with Nortraship's treatment of the war sailors, a subject close to my father's heart.

Halvor returns home to Norway after the end of the war effort and encounters many disappointments, not least of which is the shameful treatment of the war sailors; specifically, how they were betrayed with regard to the money they were supposed to have received from the much-discussed Nortraship fondet (Nortraship’s Seamen’s Fund).

It is also important to mention the War Sailor Register, a register of all the Norwegian men and women who sailed for neutral countries, for Nortraship, the Norwegian Domestic Fleet, the Royal Norwegian Navy, Allied and neutral merchant ships, and in Allied navies. International seafarers who sailed for Nortraship and in the home fleet are also registered. To date, 69,181 seafarers have been registered, around 57,540 of whom sailed for Nortraship. Some 30,003 of the latter are Norwegians, and 27,537 are international seafarers. There are 5,202 ships registered.

The register gained momentum when the Samlerhuset (The Collectors’ House) came into the picture, coinciding with my father appearing on NRK Kveldsnytt (Norwegian television), and pointing to the Norwegian Peace and Human Rights Centre Archive as the proper institution to be given national responsibility for documenting the history of the war sailors. Samlerhuset (a Norwegian distributor of collectibles, mainly coins and medals) provided most of the funding at the start, and over the years volunteers at the Seamen’s Association have put in a significant amount of work digitising the information. In particular, I would like to mention the Lillesand Seamen's Association.

The ARKIVET Peace and Human Rights Centre has also invested a considerable portion of its own funds. Since the start of 2016, the state has contributed by funding two full-time positions in the Centre of the History of Seafarers at War.

Norwegian Shipping and Trade Mission (Nortraship) was the world's largest shipping company and its importance during the war was crucial to the Allied effort. Nortraship's operations also helped to secure income after the war by ensuring that there was a partially intact industry in 1945. The profits from these voyages were used to create a fund that was intended to benefit the sailors, however, the use of the money created a great deal of acrimony and strong debate. It was not until 1972, following the recommendation of the Nortraship committee, that this dispute was put to an end, and the war sailors were finally paid a lump sum for the war voyages they had participated in during the Second World War.

The war effort was costly. If we add the losses in the home fleet, 3,211 Norwegian sailors lost their lives in warships, and 764 Norwegian ships were lost. Furthermore, 953 foreign seamen perished in wartime shipwrecks in the outer fleet.

Half of the Norwegian sailors experienced being torpedoed during the war, some as many as four times, and facing the ongoing possibility of death was an enormous strain that had long-lasting consequences. When peace came there was no shortage of beautiful words for the war sailors, however, when the survivors finally returned home the thanksgiving had largely died down. Honour was replaced by oblivion and even contempt. Again and again, the sailors had to fight to provide concrete evidence of what their effort had meant and what it had cost. Some ended up as alcoholics or homeless people, with little help from society. Others struggled with both physical and psychological injuries from the war.

The Norwegian authorities' treatment of Norway’s sailors after the war has been strongly criticised. Now, 80 years after the war - there is an almost complete list of tens of thousands of seamen who served in the Merchant Navy and who put their lives on the line, but did not receive the thanks they deserved until recent times. It is way too late, but it’s time.

Tania Michelet

Moss, Norway, September 2023

….

Oscar Andersons war medals. Photo by Roger Albrigtsen

READ THE FIRST PUBLISHED NEWS ABOUT OSCAR/SAKEN FRA NRK:

Norwegian text (click)

English translated text click here to read or read below:

The last war sailor

The last Norwegian war sailor in Britain may end up living in a caravan. In a British nursing home, he celebrates his 102nd birthday and looks back on a dramatic life.

«Gry Blekastad Almås Correspondent

We are reporting from Shropshire, England

There is barely room for an armchair next to the single bed in room number 30. In it sits 102-year-old Oscar Anderson with a brand new medal around his neck.

These nine spartan square meters in a British nursing home have become the Norwegian war sailor's last stop for the time being.

But he may have to move into a caravan.

I am visiting the aging war hero to talk to him about the war. He is probably the last surviving war sailor in Great Britain. Many war sailors settled in the British Isles when the return to Norway after the war did not go as expected.

Oscar Anderson was actually called Andersen and comes from Tjøme in Vestfold. While still a teenager, he went to sea. Then came the war.

He became one of those who carried out some of the most dangerous operations for the Allies during the Second World War. It is people like him that we can thank for the freedom we have today.

102nd birthday in a nursing home

Some young, aging voices fill the nursing home's living room: "Happy birthday to Oscar. Happy birthday to you". The birthday child is struggling to blow out the candles on the birthday cake. Balloons and Norwegian flags adorn the walls and ceiling.

Oscar has invited me to his 102nd birthday celebration. We are eight guests in total, myself included.

The retired sea captain Wiktor Mølleskog stands up. He has been given the honor of presenting two new medals to the aging war sailor. On his lapel hangs three he has from before.

He accepts and feels the new medal. Oscar sees almost nothing anymore. But he is happy to be appreciated. It wasn't like that before.

"Norway's most important contribution to the Allies' victory during the Second World War", writes the Norwegian Defense Forces about the war sailors today. But the task of transporting fuel, soldiers, weapons, steel and other war-important goods was anything but harmless.

Was torpedoed

German submarines threatened in the sea below the ships. Above them were Nazi bombers. Oscar Anderson knows what it means to be terrified.

It is 80 years since his ship was torpedoed on its way from Liverpool to New York. He was standing on the bridge looking out when there was a crash in the engine room. He realized then and there that the two colleagues from Larvik died together in there.

Oscar had to persuade the captain to get into the lifeboat. It saved both the captain's life, his own and several others' lives. Ten minutes later, another torpedo sank the damaged ship.

Once on board the lifeboat, someone started shooting at them. They were unable to start the engine, and the oars took hold. They rowed for their lives. It was allies who fired. In the February darkness, they thought the lifeboat was one of the 18 German submarines that attacked.

After a while they were picked up by a British ship in the convoy. There, Oscar helped save the life of the crew who had fired at them. Their ship was also hit by a torpedo. Now they were the ones who came in lifeboats. One man died in his arms.

14 boats went down that night. 400 sailors lost their lives. Oscar saw people drowning, they left desperate people in the waves. He lives with the memories.

The difficult homecoming

He asks me if I think he seems "right". I answer in the affirmative. He remembers details from 80 years back, and longer than that too. He is quick in his retort and tells stories easily.

He asks how he appears because I have just asked him how he was affected by the dramatic events. Many war sailors became mentally ill from the traumatic experiences. Alcohol was a frequently used drug. It didn't go well with everyone.

Nor did they receive the welcome that war heroes deserve. They were distrusted, including Oscar. He says that people back home in Norway thought he had sneaked away from the war. That he had lived abroad in a hurry.

He was not paid the salary he should have been, and struggled to get a job. He became bitter and wanted nothing more to do with Norway.

He went back to Britain. And here he has remained.

Asking Norway for help

And then Oscar tells me something that hurts. I don't quite know what to say. He says that now he would rather die. It's boring in the nursing home. He has been here for three months. He does not see, has no one to talk to. "I'm sitting here like an idiot," he says.

Three months ago, his wife ended up in a wheelchair and is no longer able to take care of him. But care costs a lot, close to NOK 100,000 a month. The municipality only covers the expenses for people with less than NOK 300,000 in savings. Oscar and his wife have just about that.

Oscar's Norwegian war pension goes to pay the bills, but now his wife is considering selling items they have in the house. If she also ends up in a nursing home, the whole house will go up in flames.

There are often cases in the British media about families having to sell their houses to finance nursing home stays. There are many who are dismayed by a system that is so complicated that even people in the healthcare system do not understand it.

There is a big debate about the shortcomings in care for the elderly. Oscar's wife has tried to find other and cheaper alternatives, but she has not been able to.

In desperation, she has written a letter to NAV (the Norwegian NAV handles pensions). Because Oscar receives a war pension from Norway, she believes that he may also be entitled to Norwegian support for his nursing home stay. She is still waiting for an answer.

Norwegian law covers "medical treatment for injury or illness approved as war damage".

Could end up in a caravan

Meanwhile, the son is applying to set up a caravan in the garden. It's not an ideal home for a nearly blind 102-year-old and an 83-year-old wheelchair user, but it's something they can afford.

Thus, one of Norway's war veterans, one of those who gave us our freedom, can end his life as a camper.

When Oscar Anderson looks back on his life, there is one thing he regrets: He should have kept the Andersen name. "You have to be who you were born to be." He wishes he was still a Norwegian citizen. He wants to die as a Norwegian.

But it won't be like that, he realizes.

I brought "a little piece of Norway" with me as a birthday present. Norwegian milk chocolate. But now Wiktor Mølleskog has decided that we can give him one more thing from Norway, he and I. As the only Norwegian guests present, we clean our vocal cords, put aside all shame and vote in - in Norwegian:

"Hooray for your birthday, yes we would like to congratulate you."».

(Text has been google-translated)

Co-organizers2

Co-organizers2

Roger Albrigtsen

Organizer

Lakselv, 20

Wiktor Molleskog

Co-organizer