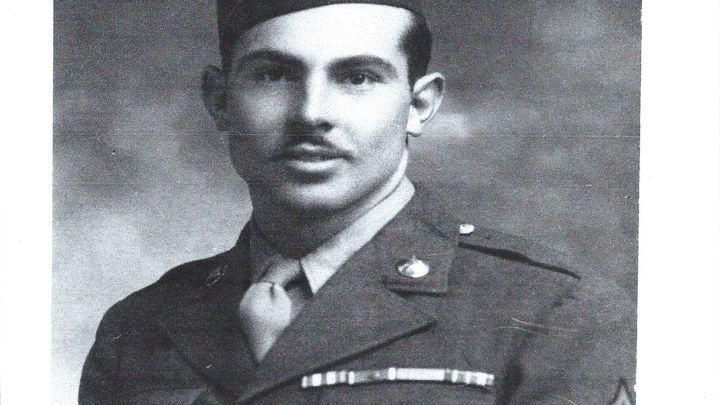

D-Day veteran

Donation protected

June 6, 1944, became famous for D-Day, the Allied invasion of France that led to the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Ray Lambert, a combat medic, was with the first assault wave on Omaha beach (see the story of his actions that day, below).

Ray ran back and forth on the beach, exposed to heavy enemy fire, to bring casualties to this rock for treatment. Ray was badly wounded during these efforts.

There are many memorials at Normandy, but none dedicated to the combat medics who saved so many lives that day.

Thanks to the efforts of Normandy resident Christophe Coquel (pictured with Ray), the Government of France has agreed to have a plaque for the Combat Medics who served with Ray on Omaha Beach.

The cost of the plaque is $3775, which Christophe will need to pay from his own pocket if we cannot support him.

Ray is nearly 98 years old and will make what will probably be his last trip to Normandy for the ceremony. He recently recovered from a severe case of bronchitis.

We would like to offset the costs of Ray's airfare and lodging, too. Ray grew up in Depression-era Northern Alabama, so he will not spend $$ for a business class ticket. The next priority would be to get his ticket upgraded so he can lay flat on the overnight flight from Charlotte, NC.

Funding beyond that will offset the costs of producing Ray's official memoirs (he has an incredible life story, too).

Any remaining funds will be donated to a charity of Ray's choice.

Here is the story of Ray on Omaha Beach, excerpt from his Memoirs:

Everyone experienced D-Day in his own way.

Ray’s experience as a combat medic in the first wave assault on Omaha Beach defined him, just as Ray’s prior experiences defined his actions on D-Day.

June 6, 1944. 0630 AM. The crash of naval gunfire and aerial bombing grew louder. Ray’s Higgins boat, one of hundreds in the first wave, floundered in the Channel, slowly edging toward the overcast beaches of Normandy. Ray breathed in the diesel fumes from the engine and the sour sickness that sloshed around his feet – the remnants of a very nice breakfast.

Plumes of water shot up around his boat as German shells detonated around them. Occasionally, a boat exploded into flames and death.

Staff Sgt. Ray Lambert, leader of the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, medical platoon, crouched in the front left seat of the troop compartment. A hailstorm of bullets from German machine guns pelted the sides as the distance to the beach closed. Of the 31 men crammed together that morning, only seven would be alive by dusk.

Ray thought of his brother. Bill was the G Company first sergeant in the 16th Infantry, probably scores of boats to the west. The nervous chatter in the boat stopped long ago, as soldiers tried not to imagine what lay ahead.

Fear. Adrenaline. Stay calm. Think of something else.

Ray had landed with the 1st Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily, but nothing compared to the violence of this landing. He knew he had to un-ass the boat quickly. As the ramp came down, the open front of the boat would funnel the bullets inside, ricochets tearing through flesh and bone.

Ramp down.

Ray jumped into neck-deep water, struggling with his equipment to stay upright and move forward into heavier concentrations of bullets and shells and fragments. Bullets tore through the inside of his boat as Ray entered the water. Many of his 30 companions would not even make it into the water alive.

As a medic, Ray wore a white armband with a red cross on his arm and a similar design painted on his helmet. Medics were supposed to be protected from targeting by the Geneva Convention, but everyone knew that wounded soldiers sapped far more combat power than dead ones. Killing the medics meant combat soldiers would need to treat the wounded. The Red Cross provided a good aiming point for German marksmen.

“Keep moving!” Ray yelled to a drowning soldier that he pulled onto the shore.

The air was full of whistling bullets and the whoosh of shells and fragments. The 16th Infantry had landed in front of a German bunker. The enemy’s machine gun sights were trained on the exact point Ray came ashore.

Time slowed. Men struggled with the surf, concussions, and growing accuracy of the German fire.

Tunnel vision. Everything to my front is in sharp focus. I hear the crash of shells and the screams of the wounded. I’ve got to find a place to bring the casualties.

Ray noticed a large hunk of concrete to his front – the only cover on that beach. He quickly decided that, for now, that would be the best place to treat the wounded.

He positioned one of his medics, Corporal Ray Lepore, at the rock. “Stay here and treat the casualties I bring.”

Ray charged back into the surf, away from the protection of the concrete boulder, to pull in more of the drowning and wounded. He returned time and again.

Damn!

Ray was shot near the elbow. “That one just pissed me off,” Ray told me 60 years later.

He continued his grim mission between the big boulder and the Channel surf – rescuing the drowning, treating the wounded, comforting those who had only moments left to live. How he had survived so exposed on the beach for as long as he did was a miracle.

Ray brought another casualty to Lepore and charged back toward the surf.

A piece of shrapnel hurtled through the smoke and tore a chunk out of his left leg, forcing Ray to the ground. Damn, that one hurt!

Bleeding profusely, Ray matter-of-factly injected himself with morphine, applied a tourniquet to his leg, and drove on.

Sixty-nine years later he was convinced that he was active on the beach only for a few minutes. In fact, it was over an hour; exposed to intensive fire the entire time.

Ray noticed more Higgins boats coming in – that would be the second wave, due around 0730. Ray spied another drowning soldier and raced back into the water to drag him to safety.

Crash! As Ray was pulling the soldier to safety, a Higgins boat roared in behind him and dropped the ramp directly onto Ray’s back, trapping him beneath the water. He was held to the floor of the Channel for what seemed an eternity. If I’m going to die, at least let it be from enemy fire and not drowning.

The pressure eased. Ray and the other soldier gasped for breath. When he was finally able to move again, he was in terrible pain.

He stumbled toward the rock. Adrenaline was the only thing keeping him moving. You’re good now, go forward!

Ray began to feel the effects of blood loss, fatigue, and a broken back. He told Lepore, the young medic, to take over the rescue efforts, while Ray used his remaining strength to treat the wounded sheltered behind the rock.

But when Lepore stood up to help, a bullet rammed through his skull. He died immediately, falling onto Ray’s back and causing Ray to black out from the pain.

Ray Lambert, a combat medic, was with the first assault wave on Omaha beach (see the story of his actions that day, below).

Ray ran back and forth on the beach, exposed to heavy enemy fire, to bring casualties to this rock for treatment. Ray was badly wounded during these efforts.

There are many memorials at Normandy, but none dedicated to the combat medics who saved so many lives that day.

Thanks to the efforts of Normandy resident Christophe Coquel (pictured with Ray), the Government of France has agreed to have a plaque for the Combat Medics who served with Ray on Omaha Beach.

The cost of the plaque is $3775, which Christophe will need to pay from his own pocket if we cannot support him.

Ray is nearly 98 years old and will make what will probably be his last trip to Normandy for the ceremony. He recently recovered from a severe case of bronchitis.

We would like to offset the costs of Ray's airfare and lodging, too. Ray grew up in Depression-era Northern Alabama, so he will not spend $$ for a business class ticket. The next priority would be to get his ticket upgraded so he can lay flat on the overnight flight from Charlotte, NC.

Funding beyond that will offset the costs of producing Ray's official memoirs (he has an incredible life story, too).

Any remaining funds will be donated to a charity of Ray's choice.

Here is the story of Ray on Omaha Beach, excerpt from his Memoirs:

Everyone experienced D-Day in his own way.

Ray’s experience as a combat medic in the first wave assault on Omaha Beach defined him, just as Ray’s prior experiences defined his actions on D-Day.

June 6, 1944. 0630 AM. The crash of naval gunfire and aerial bombing grew louder. Ray’s Higgins boat, one of hundreds in the first wave, floundered in the Channel, slowly edging toward the overcast beaches of Normandy. Ray breathed in the diesel fumes from the engine and the sour sickness that sloshed around his feet – the remnants of a very nice breakfast.

Plumes of water shot up around his boat as German shells detonated around them. Occasionally, a boat exploded into flames and death.

Staff Sgt. Ray Lambert, leader of the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, medical platoon, crouched in the front left seat of the troop compartment. A hailstorm of bullets from German machine guns pelted the sides as the distance to the beach closed. Of the 31 men crammed together that morning, only seven would be alive by dusk.

Ray thought of his brother. Bill was the G Company first sergeant in the 16th Infantry, probably scores of boats to the west. The nervous chatter in the boat stopped long ago, as soldiers tried not to imagine what lay ahead.

Fear. Adrenaline. Stay calm. Think of something else.

Ray had landed with the 1st Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily, but nothing compared to the violence of this landing. He knew he had to un-ass the boat quickly. As the ramp came down, the open front of the boat would funnel the bullets inside, ricochets tearing through flesh and bone.

Ramp down.

Ray jumped into neck-deep water, struggling with his equipment to stay upright and move forward into heavier concentrations of bullets and shells and fragments. Bullets tore through the inside of his boat as Ray entered the water. Many of his 30 companions would not even make it into the water alive.

As a medic, Ray wore a white armband with a red cross on his arm and a similar design painted on his helmet. Medics were supposed to be protected from targeting by the Geneva Convention, but everyone knew that wounded soldiers sapped far more combat power than dead ones. Killing the medics meant combat soldiers would need to treat the wounded. The Red Cross provided a good aiming point for German marksmen.

“Keep moving!” Ray yelled to a drowning soldier that he pulled onto the shore.

The air was full of whistling bullets and the whoosh of shells and fragments. The 16th Infantry had landed in front of a German bunker. The enemy’s machine gun sights were trained on the exact point Ray came ashore.

Time slowed. Men struggled with the surf, concussions, and growing accuracy of the German fire.

Tunnel vision. Everything to my front is in sharp focus. I hear the crash of shells and the screams of the wounded. I’ve got to find a place to bring the casualties.

Ray noticed a large hunk of concrete to his front – the only cover on that beach. He quickly decided that, for now, that would be the best place to treat the wounded.

He positioned one of his medics, Corporal Ray Lepore, at the rock. “Stay here and treat the casualties I bring.”

Ray charged back into the surf, away from the protection of the concrete boulder, to pull in more of the drowning and wounded. He returned time and again.

Damn!

Ray was shot near the elbow. “That one just pissed me off,” Ray told me 60 years later.

He continued his grim mission between the big boulder and the Channel surf – rescuing the drowning, treating the wounded, comforting those who had only moments left to live. How he had survived so exposed on the beach for as long as he did was a miracle.

Ray brought another casualty to Lepore and charged back toward the surf.

A piece of shrapnel hurtled through the smoke and tore a chunk out of his left leg, forcing Ray to the ground. Damn, that one hurt!

Bleeding profusely, Ray matter-of-factly injected himself with morphine, applied a tourniquet to his leg, and drove on.

Sixty-nine years later he was convinced that he was active on the beach only for a few minutes. In fact, it was over an hour; exposed to intensive fire the entire time.

Ray noticed more Higgins boats coming in – that would be the second wave, due around 0730. Ray spied another drowning soldier and raced back into the water to drag him to safety.

Crash! As Ray was pulling the soldier to safety, a Higgins boat roared in behind him and dropped the ramp directly onto Ray’s back, trapping him beneath the water. He was held to the floor of the Channel for what seemed an eternity. If I’m going to die, at least let it be from enemy fire and not drowning.

The pressure eased. Ray and the other soldier gasped for breath. When he was finally able to move again, he was in terrible pain.

He stumbled toward the rock. Adrenaline was the only thing keeping him moving. You’re good now, go forward!

Ray began to feel the effects of blood loss, fatigue, and a broken back. He told Lepore, the young medic, to take over the rescue efforts, while Ray used his remaining strength to treat the wounded sheltered behind the rock.

But when Lepore stood up to help, a bullet rammed through his skull. He died immediately, falling onto Ray’s back and causing Ray to black out from the pain.

Organizer

Christopher Kolenda

Organizer

Washington D.C., DC