- D

- K

- K

THANK YOU to everyone who made it possible to reach the goal funding the printing of 500 books to send to Uganda! I’m so grateful for the support from friends, family, and acquaintances in all corners of my life. $3150 seemed like a lofty goal, but we managed to reach it even sooner than I expected. Going forward, any additional donations will be directed towards hiring translators, printing books in additional languages, and transforming the content into a video format. Thanks again for your contributions! I can’t wait to see where this goes, hopefully this is just the start.

Original Goal

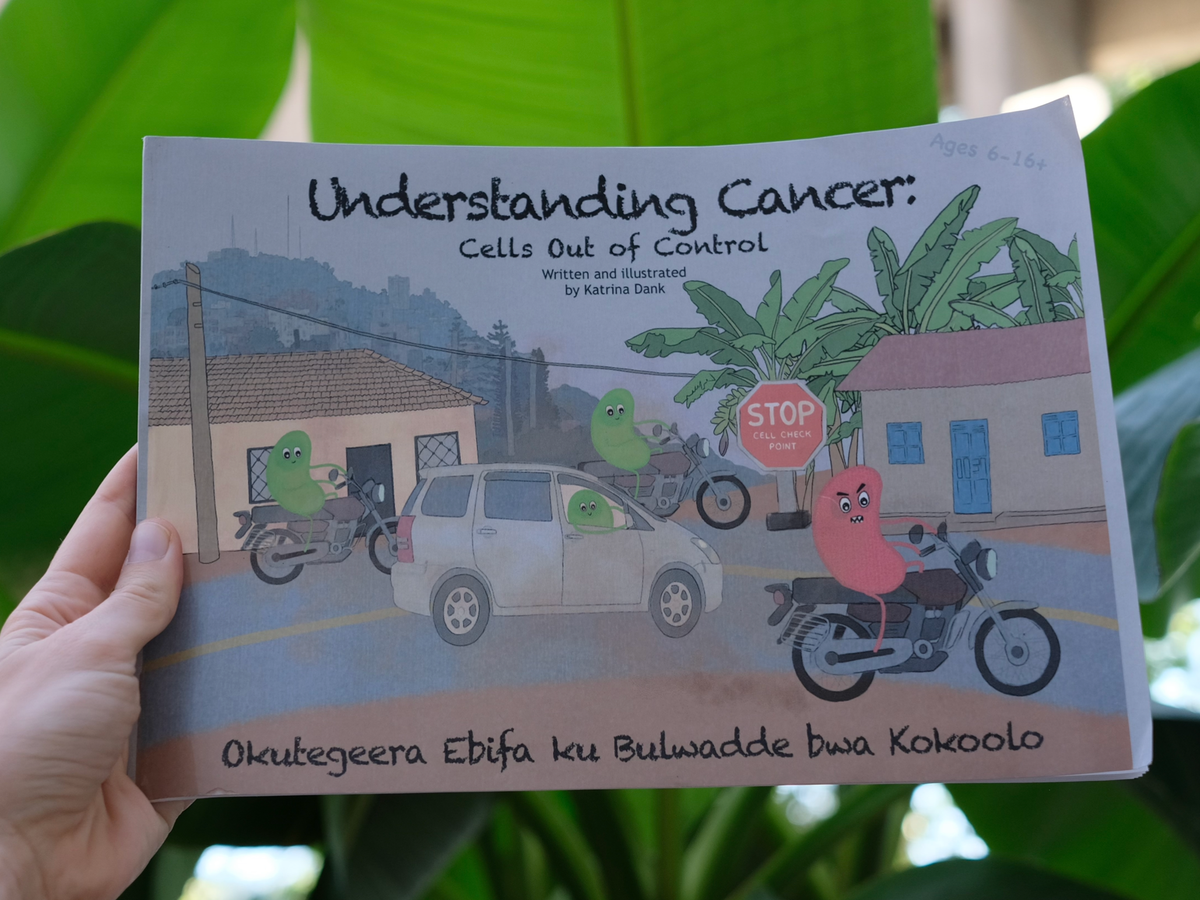

Every $6.30 donated will fund the printing of one hardcover copy of Understanding Cancer: Cells Out of Control. The current goal of $3150 will cover the printing of 500 books destined for schools and cancer care sites across Uganda. International shipping is graciously provided at no additional cost by Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in partnership with the Hootie Lab.

Going Forward

I am working with a professor at UW to expand the reach of the book beyond Uganda. Thus far, we have identified eight additional target languages and are working to establish distribution partnerships. If you have any relevant connections in this field, I would love to hear from you.

If you donate more than $25 and are interested in a copy of your own, please fill out the following google form . Please note the initial print job will take at least 5-7 weeks.

I’ve been taken aback by the support I’ve received for this project every step of the way and am so grateful for my community both in the US and Uganda for making this all possible. Thanks again for your contributions!

THE STORY OF THE STORY

This summer I had the opportunity to participate in University of Washington’s Global Health Immersion Program and spend 8 weeks working at the Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) in Kampala, Uganda. Having only finished one year of medical school, I did not have the skills to ethically provide medical care. Instead, we were tasked with identifying a community need and designing a project to address it. Through this program design, we were permitted multiple weeks to do nothing but get to know the patients, parents, providers and community members of the community we were living and working in. I was so grateful for the opportunity to engage in these meaningful interactions without a strict agenda. In medical settings, especially global health, funding is often limited and earmarked to achieve strategic goals. As an unpaid student completing coursework, my only constraint was that my project had to align with UCI’s goal of improving cancer care for their community.

When we think of developing nations like Uganda, we tend to focus on the burden of communicable diseases. This in many ways aligns with the global burden of disease, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cause of death by disease type for Uganda (left) and United States (right). Each box indicates the proportion of deaths attributed to the labeled cause, with the entire square representing 100% of deaths in the country. Red represents communicable diseases, blue represents non-communicable diseases, green represents accidents. Deaths attributed to cancer are outlined in yellow. Data visualization provided by the IHME.

Places like Uganda have received millions of dollars of international funding ear marked for diseases like HIV, malaria, neonatal health, and tuberculosis. However, when speaking with locals, I quickly realized cancer is one of the most significant health concerns of community members across Uganda. In a casual conversation at trivia, a journalist Hasne said “cancer is the new HIV.” When exploring the far wetern region of Uganda just a hill away from the Democratic Republic of Congo, my tour guide John identified malaria and cancer as the two biggest health problems facing his community and was able to identify the top types of cancers and relevant risk factors despite no formal medical education. The literature confirms Uganda’s high cancer burden. While broad comparative data is limited, a study by the international agency for research on cancer found Uganda had the highest incidence of pediatric cancer in the world (2). Naturally, you may wonder, why does Uganda have such an outsized cancer burden? From an epidemiological perspective, many cancers , especially pediatric cancers, are associated with HIV including Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Burkitt’s Lymphoma (originally discovered at UCI in 1958). The high numbers reported may also be partially attributed to reporting bias, with the historical presence of a revered cancer institute like UCI leading to increased cases recorded. But largely, the reason is unknown, which is why institutions like Fred Hutchinson have partnered with UCI.

Uganda Cancer Institute is the only public cancer-specific treatment facility in Uganda. When I arrived, I was split on which department I wanted to focus my time in. As an aspiring pediatrician, I was highly interested in working in the outpatient pediatric oncology clinic. However, due to the nature of our project and skill sets, the Comprehensive Community Cancer Prevention (CCCP) department’s focus on educational outreach better aligned with my skill sets and interest in educational interventions. They conduct cancer screenings, host daily risk factor prevention seminars, and travel to health fairs across Uganda to educate communities and conduct further screenings. Meanwhile, the outpatient pediatric oncology clinic consists of three or four doctors overseeing cancer diagnoses and coordinating treatment. Doctors see anywhere from 25 to 75 patients a day and families wait hours to see them in the waiting room or on colorful picnic mats scattered across UCI’s campus. After a couple weeks working with both groups, it became clear that my dilemma of having to choose between pediatrics or educational outreach represented a systemic shortcoming my project could address. While the CCCP has an impressive educational curriculum, the materials are aimed at adults and written in only a handful of languages. Meanwhile, the pediatric oncology clinic does a wonderful job of treating the medical needs of their patients but lacks the time and capacity to provide education. By creating an image-based resource covering basic principles of cancer I could provide key information to a previously unreached audience of children, those with low literacy, or anyone who speaks one of the non-primary languages in country with 52 languages.

In my first weeks I had a memorable conversation with the father of a little boy who was in remission for blood cancer. I asked how he told his son who was only six years old at the time that he had cancer and if he had any resources on how to explain such a difficult condition to a child. He said he navigated the process alone, not knowing how to explain it to his son other than that he was “really sick”. I wanted to make this process easier for both the patients and parents and so I set out to write a children’s book they could turn to when navigating this challenging reality. Over the course of 32 pages of colorful anthropomorphized cells, Understanding Cancer: Cells Out of Control does exactly that.

Not only does the book explain what cancer is, but in doing so it challenges common misperceptions and promotes successful treatment behaviors. Some of the key content goals achieved by the book include:

- Providing a scientific, cell-level explanation for understanding cancer - The primary analogy for cancer revolves around angry-looking red cancer cells disobeying police checkpoints, a sight ubiquitous throughout Uganda. In Uganda, one of the biggest challenges with cancer care is overcoming pervasive beliefs that cancer can be cured by reversing a curse or taking an herbal remedy. It doesn’t help that individuals who doubt the medical system most tend to present to medical care later, thereby increasing the likelihood of having further progressed disease, limiting the efficacy of treatment and in turn creating a community association with hospitals and bad outcomes. By providing a scientific understanding of what cancer is, we can rationalize evidence-based treatment methods, possibly even in conjunction with more spiritual approaches.

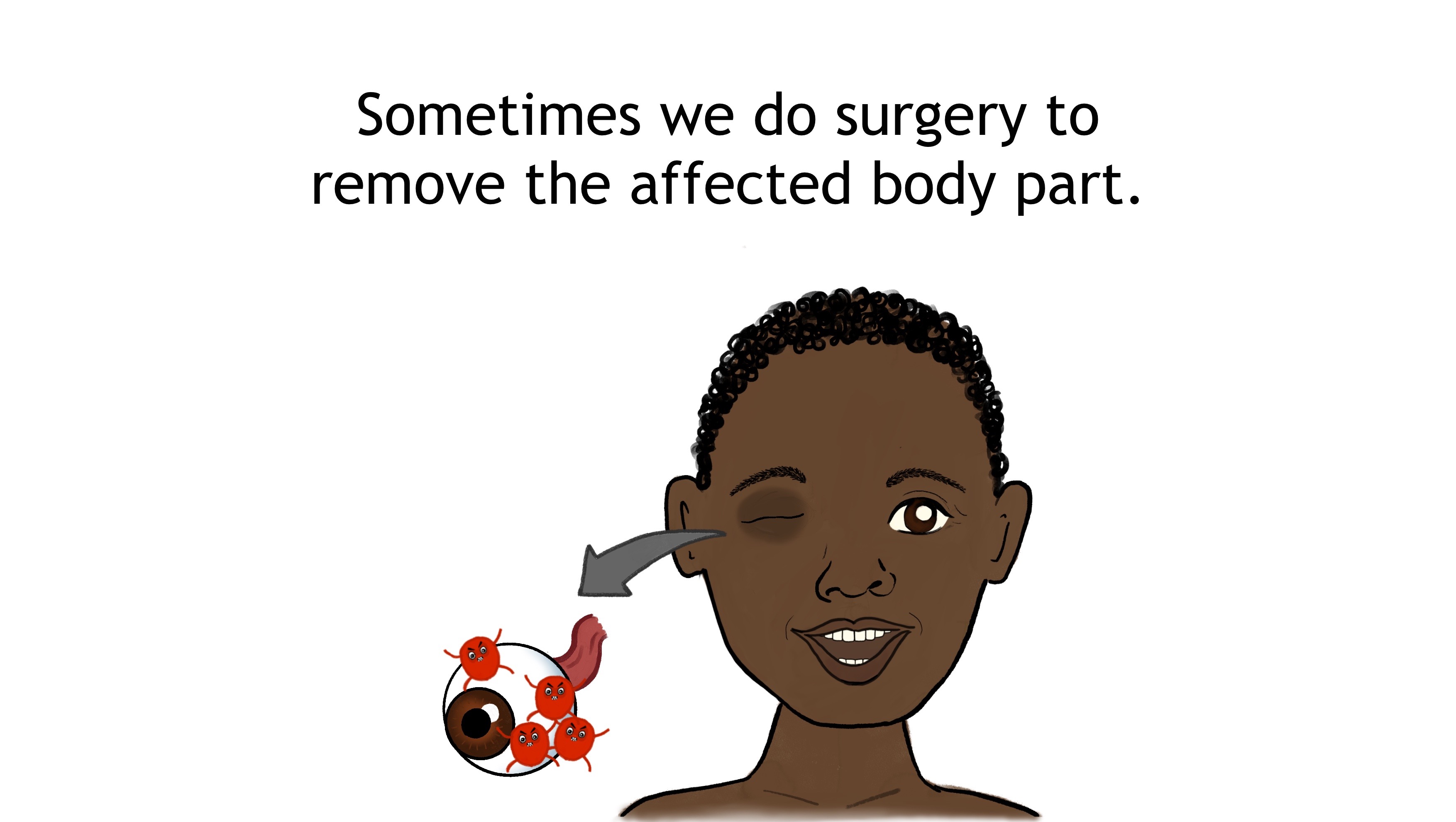

*GoFundMe only allows a single image size, all book pages include a Luganda translation at the bottom of the page which has been cropped due to size limitations

- Reducing stigma - A cancer diagnosis can be incredibly stigmatizing. People fear “catching” cancer, community members don’t understand the realities of treatment, and even once patients are in remission, they are viewed to be flawed or less deserving of opportunities.

- Normalizing the patient experience - Treatment varies between individuals and can be understandably frightening. It is important to prepare children for what this may look like. Additionally, it is good to normalize some of the consequences of treatment whether that be a patient losing a body part or being unable to participate in activities due to chemotherapy side effects.

- Encouraging early presentation to medical facilities - Time and time again it has been found that the earlier cancer treatment is started, the more likely someone is to survive. It’s simple math of preventing the accumulation of malignant cells. We want patients to go to a doctor as soon as they notice an abnormality rather than trying other methods and losing valuable life-saving time. (It’s important to recognize that many of the challenges this book attempts to address are not simply a matter of an individual’s attitudes or misperceptions, but a broader reflection of social determinants of health. For many, seeing a doctor requires a significant investment of time and resources. With limited cancer care sites available throughout Uganda, people can travel upwards of 20 hours on unreliable public transit and bumpy roads. They often have to choose between investing in the journey to medical care and other daily living expenses.)

- Providing a rationale to reduce loss to follow-up care - Once patients look and feel healthy, it is hard to understand why the costs, side effects, and relocation required by cancer treatment are necessary. Unfortunately, cancer cells can continue to grow and spread even after a patient looks better on the outside. Not only does this book state the importance of following doctor’s directions, but it connects the need for follow-up to what is happening at a cell level.

- Educating the community on risk prevention strategies - While pediatric cancers are largely non-preventable, just because you have one type of cancer doesn’t mean you can’t develop another type of cancer. At a community level, sharing risk prevention strategies is one of the most impactful ways to reduce future cancer burden. Additionally, children are known to go out and educate their parents and communities on health-promoting behaviors. Of the 8 strategies included, my advisor and I went back and forth on whether to include not microwaving plastics. Microwave use in Uganda is relatively uncommon and isolated to urban centers. However, I argued that this means Ugandans are less likely to have microwave-safe plastics and be aware of this contraindication, a risk which will only increase with the inevitable adoption of microwave technology with time. When I met with the high school club committees, one of the students specifically noted how he had never heard of this advice and would be educating his community going forward.

- Reinforcing learning through a self-directed quiz - There’s no better way to summarize the key points of a book than to provide an activity for recall at the end of the reading experience.

- Rewarding rereading materials by providing stickers for each time the book is read - A couple hundred colorful cancer cell stickers were made to give to children as a reward after reading the book. Ideally, each time a patient visits the clinic they can read the book and receive a new colored sticker to promote reinforcing the information covered in the book.

Illustrations:

I drew all the illustrations on my iPad using the app Procreate. Throughout the process people kept asking if I like to draw. I’ve never been one to prioritize my free time doing art, but I have spent the last decade+ making detailed visually appealing study sheets for my STEM classes. I briefly met with an illustrator at Mulago Hopsital’s Medical Illustration Department. He showed me some of their amazing work and walked me through his approach to projects. In this meeting I learned a single page of detailed illustrations can cost $400 USD, reinforcing my value in providing free illustration labor, albeit untrained. The illustrator also emphasized the importance of using simple images to clearly communicate the target messages to a pediatric audience. I was torn, as my favorite children’s books growing up had bright colors and intricate scenes. In the end, the style of the book aimed to strike a balance between big bold colors and simple more subdued background contexts to increase message clarity.

It was very important that the images included in the book reflect the experiences of the children reading it. Some specific visual choices made to align with the culture include:

- The primary analogy revolving around common Ugandan vehicles and the phenomenon of police checkpoints

- Characters who look Ugandan

- Hide and seek, but in banana groves which I saw almost every time I got out of the city

- A swing set rather than a soccer game because it is a gender-neutral activity

- Representing typical Ugandan diets in food depictions

- Avoiding red and yellow stickers to avoid political party associations

Translations:

The primary language for medical care at UCI is English, however Uganda is known to have 52 distinct language groups. For the initial copy of the book, I chose to include a second line of Luganda text as it is the primary language for the Central Region of Uganda where UCI’s main campus resides. Initial online translations were edited by a local medical student peer, Jacob Malaga, and further reviewed by UCI’s team of trained translators including Jacqueline Asea, Ruth Nakuya, and Constance Namirembe.

Partners:

The original intention of the book was solely as a resource for patients passing their time waiting to see physicians in the outpatient pediatric department. However, as word spread of my project, multiple other departments and community organizations requested copies. When I left an initial round of 18 books were printed and distributed across five pediatric care settings. These included:

- The inpatient pediatric oncology ward playroom

- Always available with book collection

- Staff members conduct weekly readings

- Outpatient pediatric oncology clinic waiting room

- Multiple copies available at the check-in desk

- Stickers provided as motivation for each time a patient reads the book

- Staff members conduct weekly readings

- Comprehensive Community Cancer Prevention (CCCP) outreach -

- A poster version of the material was made to align with existing presentation strategies.

- Three hostels in Kampala for children and their caretakers tp stay while receiving care away from home

- A total of 82 patients and 82 caretakers

- UCCF’s Children Caring about Cancer (3C’s) clubs

My partnership with the Uganda Child Cancer Foundation (UCCF) was a major turning point in the project. While waiting in line for food after a conference, I found myself talking to the leader of the Uganda Cancer Society. He suggested I reach out to UCCF, which I had yet to hear of. Within a few days I found myself randomly knocking at UCCF’s office door - a testament to how most things in Uganda operate by word of mouth. UCCF has a 3C’s club program in 238 secondary schools across Uganda. They had been looking to expand the program to primary schools, but lacked the necessary materials or curriculum. This book provided the missing piece, enabling involved secondary students to go to primary schools to conduct classroom readings - dramatically expanding the reach of the book. Suddenly, my picture book designed for one waiting room had the potential to reach tens of thousands of youth across Uganda.

I want to end on a note about the power of educating children through visual storytelling with an example close to home for Uganda. At the final book release party, my mentor Dr. Fadhil Geriga gave a speech:

“At first it was for children who are waiting to see doctors and children on wards, to have some literature for them. But now when I look at this book today I remember many years back when I was very young, the game changer in Uganda’s HIV journey was like this when I was in primary school. For those of you who weren’t there, the game changer for the HIV campaign in the early 90’s was just a booklet like this dropped in all the primary schools. And it communicated through pictures in the way this one is communicating. The NPCA’s strategy was delivered through this and it really made an impact. So now when I look at this my mind goes back 30 years. We need to take advantage of this beginning to change the face of cancer among children in Uganda.”

While I was aware Uganda had one of the greatest historical burdens of HIV and was widely regarded as an international success story in reversing this statistic, I had never looked into how they achieved this response. One of Uganda's primary strategies in their first national AIDS control plan of 1987 was described as “to mount an educational campaign to inform the public on the modes of transmission and ways to avoid infection” (3). In fact, 40% of their initial budget was dedicated to health education outreach, with management, surveillance/care, and lab support being secondary financial priorities. Education, especially through simple and accessible formats, has the potential to change the world. While only 18 books are currently circulating around UCI’s campus, I hope this fundraiser can allow my book to play an important role in improving the story of cancer education and morbidity in Uganda and beyond.

If you somehow made it this far and aren’t done reading about my project, here are two more features on the project:

- UWSOM’s weekly Scholarly Spotlight

- A little more on how the project relates to my educational story in Pomona College’s Alumni News

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Nambalirwa Priscilla, Fadhil Geriga, Alfred Jotho, Mugisha Mugume Noleb, Derrick Bary Abila, Warren Phipps, and Andrea Towlerton for their advising and feedback throughout the process. The Luganda translations would not have been possible without the help of Jacob Malaga, Jacqueline Asea, Ruth Nakuya, and Constance Namirembe. Thank you to Olive Birungi, my daily lunch crew, desk neighbors, and everyone at UCI and ACCF who made me feel so welcome during my stay in Kampala. Lastly, thank you to Daniel Hill for all his support throughout the process including funding the initial round of printing.

REFERENCES

2. Parkin DM,Kramarova E,Draper GJ, et al. International Incidence of Childhood Cancer. VolII. Lyon, France: International Agency for Cancer Research; 1998; 1– 391.

3. Slutkin G, Okware S, Naamara W, Sutherland D, Flanagan D, Carael M, Blas E, Delay P, Tarantola D. How Uganda reversed its HIV epidemic. AIDS Behav. 2006 Jul;10(4):351-60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9118-2. PMID: 16858635; PMCID: PMC1544374.