33&CKD: Its time to prioritize kidney research

To the social media world, I’m the pink, bubbly and forever science-y @Laf_in_the_Lab. Up until October 2020, my purpose for using social media was to demystify and humanize science by sharing a lot of my own PhD research in pediatric cardiology, document my journey as a woman and mother navigating a career in science, technology, education and mathematics (STEM). I also sought to make it a priority to discuss some of the tough topics that go along with "not fitting" a "typical" mold in STEM, like repurposing a "nontraditional" background, juggling motherhood in academia, facing discrimination in science, prioritizing mental health, finding and sustaining healthy mentoring relationship(s)... I was happy and extremely proud of this identity, the platform and community of support that this venture nourished...and then my world began to slowly crumble apart.

Following the loss of a near-viable twin pregnancy and recovery riddled with complications, both my physical and mental health continued to deteriorate. I will never forget that day (October 15, 2020) when I got home from work, looked down at my swollen feet, and knew something was terribly wrong.

Although I tried my best not to panic or catastrophize, I have worked in science and medical education long enough to know this was serious, and although I did not share this with anyone, I admit that I truly feared that my life was in danger at the ripe age of 32.

After the initial evaluation, I was diagnosed with Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome, a condition where your kidneys are not filtering properly, leading to the swelling (fluid accumulation) and abnormal blood/urine. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, I was in and out of the emergency room (alone), waiting and waiting to get in to see a kidney specialist. About a month or so after my swelling started, I was finally able to get in to see the nephrologist (WHO IS THE BEST!) and I was scheduled for a kidney biopsy to determine the cause of my Nephrotic Syndrome.

In the meantime, I started treatment on high-dose steroids and water pills (diuretics). After 4 days on these meds, I went into the hospital for my biopsy. Over the course of the next 24 hours, I shed close to 20 lbs in water weight and my face/ankles returned to a normal appearance.

Even though I didn't have a diagnosis yet, I began to really feel better on the medications, I felt grateful to be responding to the treatment (and so quickly!), and I felt optimistic about my overall prognosis and my future health.

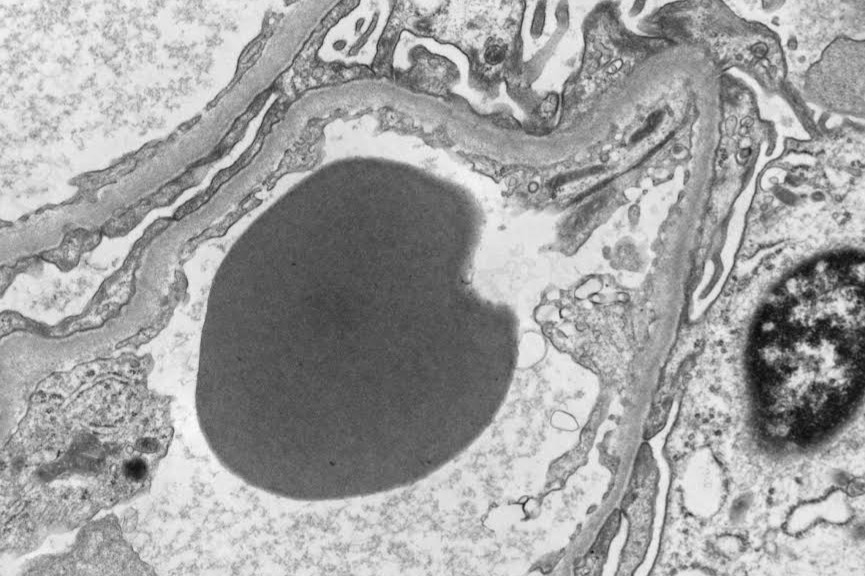

About a month later, I received my full pathology report back with a more definitive diagnosis of Minimal Change Disease (MCD). MCD is much more common in children, but can be seen in adults, and is a disease of a specialized group of cells inside the kidney called podocytes or "foot cells," due to the "feet-like" extensions these cells have that help pull waste products out of your blood. The image above is a technique called electron microscopy that looks at your cells at such a high magnification that you can see all of cell structural components (flashback to Biology 101: cell nucleus, ribosomes, plasma membrane/"cell wall"). The big grey blob in the center in a single red blood cell present within a tiny blood vessel wall (capillary) inside my kidney. With a diagnosis of MCD, my prognosis was excellent, especially given that I was responding to the drug therapy so quickly. All of the doctors agreed that the most likely, I would soon recover fully, and the disease would hopefuly not return. I clung to this, and braced myself for the intense 12 weeks of high-dose steroids that reek HAVOC everywhere in my body except for my kidneys. Sleepless nights, hair loss, facial hair growth, mood swings, irregular/painful menstrual cycles, weight gain, facial swelling "moon face", joint laxity, dry skin....the list goes on.

I passed this time by reading and learning more about my disease. I scoured every single paper and medical textbook I could get my hands on. The more I read, the more curious I became. On a burning hunch, I decided to get my entire genome sequenced to hopefully rule out a genetic cause. Little did I know, this was going to be the fortuitous impulse that was really going to drastically change my life before long. Because I did this DNA/genetic testing (sequencing), I found out that I have a very rare and spontaneous genetic mutation of the Col4A3 (type 4 collagen gene)---a diagnostic indicator for a genetic disease called Alports Syndrome. In my individual case, and because of the type/obscurity of the genetic mutation, it is most likely that I have a less severe form of the disease, but unfortunately, most of the time the answers I desperately seek are simply not known. Nobody knows.

I made it through my initial treatment period ok, and was able to slowly start tapering off the meds in early March '21. My blood and urine continued to improve drastically and I was all set to take my last doses of steroids. Then, almost as quickly as the disease has seemed to remit, it was nearly overnight that my swelling, blood and urine deteriorated and my the disease relapsed. Just two weeks before my 33rd birthday, I found myself facing the harsh reality of what was going to be my new life with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the idea that this was nowhere near close to being over, let alone cured.

I found myself (again), immersed in the scientific and medical literature, desparately seeking answers, consistency and comfort from these intellectual exercises. But there was something new this time--something I couldn't ignore--a similarity and entirely coincidental overlap with PhD research looking at embryological heart development and the role of a cell structure called the primary cilium. Most nights, I lay awake in bed completely consumed with questions---something had to be done about this, somebody needed to explore this, why wasn't anyone looking at this? And so, I decided to take matters into my own hands, literally.

After a long administrative run-around, I was able to acquire some of my own kidney biopsy to run some experiments. I recognize that this may sounds strange to many people, unorthodox, maybe even potentially indicative of someone who has lost all of their marbles. Well, the marbles might not all be there, but my scientific hunch was right, and there is a serious cause for pursuing and expanding this research further.

After a long battle with diagnostics, a painful biopsy procedure and a whole lot of waiting, worrying and wondering what my future would hold, I could not shake what felt like a sense of duty as a scientist, former clinical researcher, and passionate scientific communicator to pursue see this project through.

Enter in, 33&CKD:

To say biomedical research is expensive is a gross understatement, especially in an academic setting. What's more, while kidneys are considered a vital organ(s), they are often overlooked as secondary, “less important” targets for/of disease. This is evident even at the highest levels of scientific funding in the US, where ALL kidney diseases are often clumped into a single funding mechanism of “digestive diseases” at the National Institute of Health. It may not surprise you that science in the fields of cancer research, cardiology, neuroscience and regenerative medicine are some of the top, most-highly funded disciplines. These diseases represent an obvious need/demand from the general public (and big pharmaceutical companies). That said, the volume of funding dollars that is then left available for kidney research is slim, making grant funding nearly impossible to obtain even if you are the top in your field with an impeccable track record and every resource made available to you. I alone will not be able to change that.

However, I can use my own skills, access to information, resources, techniques/tools/tissues/medical and genetic experts to help draw attention to this category of diseases, to raise funds to generate some desperately needed, and novel, preliminary research in this field. This is what IS in my control and I intend to see it through.

Keep reading below to learn a little more about your kidneys!

Kidneys are cute, bean-shaped organs inside your belly. They are each about the size and simplicity of a small potato, but their job inside your body is far more sophisticated. These are what my kidneys look like on a CT-scan (side note: I have 2 ureters on my left side = unicorn status)

Kidneys are responsible for filtering all of the blood that is pumped through your body by the heart — this means they need to determine exactly the right chemistry of your blood (nearly instantaneously!) to make sure that you have just the right amount of oxygen, electrolytes, water, sugar, etc., and also make sure that important parts of the blood are not leaving the body by accident- for example, important blood proteins that keep your blood from clotting (or getting too sticky)inside of your blood vessels. Below is an image I took of a mouse kidney with all of the blood vessel networks outlined in purple and white.

The tubular networks inside the kidney collect all of the components of your blood that aren't needed (including any excess water), which are then filtered out of the blood and compiled to produce urine, which leaves the kidneys via a another specialized tube network, and travels to your bladder where it waits patiently (sometimes) to leave the body.

Kidneys are also considered to play a role in the endocrine system (hormones!)- where one important hormones produced within the kidney is erythropoietin ( aka “EPO”) the hormone that tells the body to make red blood cells (important!!!).