Fresco Documentation in North China

Donation protected

The temple frescoes of rural north China are being destroyed, right now, at an incredible rate. I can't stop that destruction, but I can document at least some of those frescoes before it's too late. My name is Hannibal Taubes , I'm a PhD student at UC Berkeley, originally from Boston MA. I'm raising money to fund a year-long trip into the villages of north-central China to document village frescoes, along with temple architecture and inscriptions. I believe that if I don't do this now, much of it will be lost forever.

Between 2013 and 2014, I spent a year in the villages of northern China courtesy of a grant from Harvard University, documenting inscriptions and rural temple frescoes. Even at the time, it was clear to me that I was working in a highly damaged and rapidly deteriorating environment. However, the catastrophic speed of that deterioration was brought home to me when I returned to my old research area this summer. Fully a third of the frescoes I saw three years ago are now destroyed, either by theft, by deliberate vandalism, or by neglect and structural collapse. To compound matters, at the start of the survey I had not yet developed a clear standard and technique for taking documentary photos. I was traveling mainly on foot, and so was unable to carry a heavy SLR camera. As a result, I have only have incomplete or poor-quality photographs of many of the most fragile frescoes.

Below: A 19th century wall fresco, photographed in 2013, depicting the palace of the Perfected Warrior 真武, a Daoist deity.

Below: The same room in 2017, after the theft of the frescoes. This stripping of this room haunts my dreams:

Below: Photographed in winter 2014, a 19th century wall fresco depicting the God of Horses or Hayagrīva 馬王:

Below: The same wall, photographed in July 2017. Thieves have begun to cut into it to steal the frescoes, although they haven't finished the job. Weather damage has also effaced the figures on the outer side of the wall. Photo taken by one of my volunteer documentarians:

Below: The same wall, photographed in July 2017. Thieves have begun to cut into it to steal the frescoes, although they haven't finished the job. Weather damage has also effaced the figures on the outer side of the wall. Photo taken by one of my volunteer documentarians:

Below: A 19th century fresco depicting the Dragon Kings 龍王 riding out to dispense rain. I did not take detailed documentary photos of this at the time. The fresco has now been entirely cut away and removed from the temple wall.

Seeing this destruction makes me miserable. I love these frescoes. I think they're wonderful, full of life and color and strange stories that we don't yet know. I think they're not yet understood by scholars. I want them to be preserved. And if they can't be preserved, I want them to be documented. And I think ultimately, other people will want them to be preserved and documented also. The fact that I'm spending my time not doing this, while this sack and pillage is going on around our ears, makes me miserable.

At the moment I am a second-year PhD student in the East Asian Languages and Cultures department of UC Berkeley. I spend my time reading Tibetan texts and learning Sanskrit. I will be tied down with classes for the next few years, perhaps able to leave the US for a few months at a time during summer vacations. However, after this summer's trip, my priorities have begun to shift.

These frescoes will not wait a few years. They are being destroyed now, as we speak. In another four years, very little of this material will be preserved. I have been attempting this year to obtain photographs of some particularly important sites by hiring students or funding friends to make trips, but this has been an expensive and only sometimes successful stop-gap. Someone needs to be working on this now, full time, or many of these beautiful frescoes will be lost forever.

It's also difficult to explain simply the scale of the physical and cultural destruction that's taken place in China over the last sixty years. In the 1940s, surveys north of Beijing showed that every village had between four and ten temple buildings, all with frescoes, statues, inscriptions, etc. Now, 95% of villages have no temples. A god that survives with four or five intact pre-Communist iconographies in rural north China would be considered well-attested, if anyone knew where all those iconographies were located. County-level governments might protect a few larger temple sites, but most village shrines are vulnerable to theft, collapse, or destructive renovation at the whim of the villagers. This is not Italy or France - these things are very rare and getting rarer. They need to be documented now.

My goal is to take a leave of absence from my PhD program, buy a motorcycle and a better camera than I now have, and set out again as a documentarian into the villages of north China. I will re-visit those villages where I feel that my first documentation was not thorough enough. I now have a good working relationship with the county-level cultural bureau in my main research county, so I should be able to get access to those temples which were closed to me earlier. I will then widen my survey to include the whole of China north and west of the Taihang Mountains, including the northern regions of Hebei, Shanxi, and Shaanxi provinces. I have become good at spotting old temples from satellite images (their locations within the village are seldom random), and with time I should be able to visit many or most of the sites where I'm aware village temples still exist.

If you want to understand the material and how this type of work is done, the below links give some idea. One place to look is a short piece I wrote recently titled, "Hannibal's North-Chinese Village Antiquities Search and Rescue Handbook". Although it's meant as a teaching text for my hirees and volunteers, it does explain the process of doing documentary survey work in villages, and what type of results I'm hoping to get. If you want to see documentary galleries of the type I hope to create, you can view the below iconographies of the Ladies 娘娘 , Lord Guan 關公 , the Dragon Kings 龍王 (dated to 1709) , the Mansions of the Western Seas 西洋樓 , or the Images of the Hundred Trades 百工圖 .

Below: Possibly 18th-century fresco depicting Avalokiteśvara/Guanyin 觀音 for which I do not have thorough documentation. In the 1940s, a survey counted 155 Avalokiteśvara iconographies in 212 villages. Those are all gone. I've been to 380 villages in Yu County and I know of three intact front-wall iconographies. The photograph is from 2014. I do not know if the fresco remains there now; the building in any case did not have a door and the roof is streaking mud down onto the painting.

Ultimately, my goal is to create a freely-available online database of north-Chinese village temple frescoes. This database will identify the main iconographic types and tropes and preserve and curate the extant examples for scholarly use. (I've already attempted something like this with the material I now have here, see Part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4 ; this is just an idea of what's out there and the documentary and cataloguing work which needs to be done with it.) This will include both frescoes which are damaged and frescoes which have been conserved by locals or local governments; even when such frescoes are protected in China, they are rarely reproduced in complete form or otherwise made available to scholars. Beyond just preserving images of these beautiful and rapidly vanishing frescoes, this data set could be used to answer a great number of currently open questions - what were the main gods of the north Chinese villages? What were their iconographies? What stories did they tell? When did these gods and iconographies appear? How did pre-modern rural Chinese artistic and religious traditions function? How did they relate to the "high" artistic traditions in China? What were the textual sources of these traditions? How did these village traditions interact with the Western artistic influences that began entering China from the 18th century?

Below: Possibly 17th or 18th century fresco showing the Dragon Kings 龍王 riding out to dispense rain. I have some photographs of this but not complete documentation. The photo was taken in 2014 and the building was heavily damaged structurally at that time; I do not know if the images remain there now.

At the moment, I have roughly 2000 dollars saved up for this purpose, plus a bit more in a Chinese bank account. If I can raise another $8000 to reach an even ten thousand, I will take a leave of absence from Berkeley at the end of that semester and set out with a camera into rural north China until my money runs out. I hope to do this whatever happens with or without money at the end of this year, but if I can reach my goal by the end (or beginning?) of this semester, I will leave earlier. I estimate that 10,000 dollars and a tent will allow me to survive in rural north China for perhaps eight months to a year. Up-front expenses will include: flight tickets (~$1000), a new camera (~$700) and a motorcycle (~$1000). Progressive expenses will include petrol costs, food costs, and accommodation costs when in the cities. Until I reach $10,000, I will continue to spend money on sponsoring trips to the region by friends and volunteers based in Beijing, and to sponsor my own trips during winter and summer breaks from Berkeley.

Any donation you make will ultimately get used. Even if I do not reach the goal of 10,000, I will fund a later, slower survey by working and making money from a day job. The more I get now though, the faster I can get out into the field, and the more material can be saved from theft and collapse. I will continue to put information about how this money is being used here, on my blog, and eventually on an email list if I get enough interested donors.

I believe this preservation work is important, and that anybody who cares about art or history should also think it's important. I also believe that it needs to be done now - not next year, definitely not in five years. I thank you all for your support - please forward to friends and family, anyone who has an interest in China, art, or preservation!

- Hannibal C. Taubes

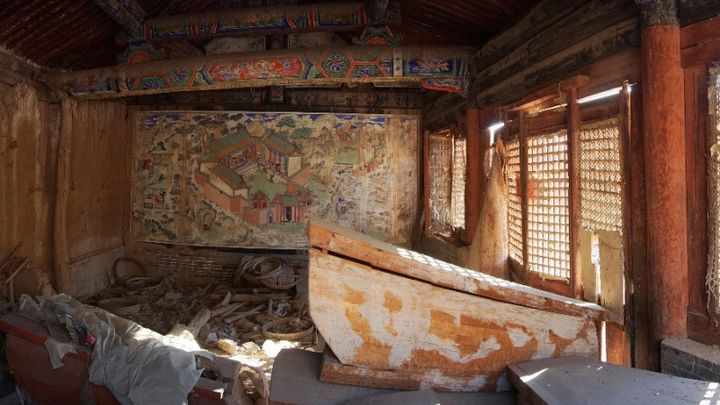

Below: Two walls of an opera stage, depicting the Jesuit-built palaces outside of Beijing, and a scene from a early 19th century popular novel. One wall is only two-thirds intact, and the collapse of part of the side of the roof has spilled mud down over most of the other wall. These frescoes were still there when I visited in July 2016, but since the stage is now kept open, it's impossible to say for how long.

Below: A shrine room dedicated to the Yama Kings 閻王, the Buddhist afterlife judges, photographed for the first time by me in July 2017. Thieves have gridded out the heavily damaged 19th century fresco for removal, apparently without success:

Between 2013 and 2014, I spent a year in the villages of northern China courtesy of a grant from Harvard University, documenting inscriptions and rural temple frescoes. Even at the time, it was clear to me that I was working in a highly damaged and rapidly deteriorating environment. However, the catastrophic speed of that deterioration was brought home to me when I returned to my old research area this summer. Fully a third of the frescoes I saw three years ago are now destroyed, either by theft, by deliberate vandalism, or by neglect and structural collapse. To compound matters, at the start of the survey I had not yet developed a clear standard and technique for taking documentary photos. I was traveling mainly on foot, and so was unable to carry a heavy SLR camera. As a result, I have only have incomplete or poor-quality photographs of many of the most fragile frescoes.

Below: A 19th century wall fresco, photographed in 2013, depicting the palace of the Perfected Warrior 真武, a Daoist deity.

Below: The same room in 2017, after the theft of the frescoes. This stripping of this room haunts my dreams:

Below: Photographed in winter 2014, a 19th century wall fresco depicting the God of Horses or Hayagrīva 馬王:

Below: The same wall, photographed in July 2017. Thieves have begun to cut into it to steal the frescoes, although they haven't finished the job. Weather damage has also effaced the figures on the outer side of the wall. Photo taken by one of my volunteer documentarians:

Below: The same wall, photographed in July 2017. Thieves have begun to cut into it to steal the frescoes, although they haven't finished the job. Weather damage has also effaced the figures on the outer side of the wall. Photo taken by one of my volunteer documentarians:

Below: A 19th century fresco depicting the Dragon Kings 龍王 riding out to dispense rain. I did not take detailed documentary photos of this at the time. The fresco has now been entirely cut away and removed from the temple wall.

Seeing this destruction makes me miserable. I love these frescoes. I think they're wonderful, full of life and color and strange stories that we don't yet know. I think they're not yet understood by scholars. I want them to be preserved. And if they can't be preserved, I want them to be documented. And I think ultimately, other people will want them to be preserved and documented also. The fact that I'm spending my time not doing this, while this sack and pillage is going on around our ears, makes me miserable.

At the moment I am a second-year PhD student in the East Asian Languages and Cultures department of UC Berkeley. I spend my time reading Tibetan texts and learning Sanskrit. I will be tied down with classes for the next few years, perhaps able to leave the US for a few months at a time during summer vacations. However, after this summer's trip, my priorities have begun to shift.

These frescoes will not wait a few years. They are being destroyed now, as we speak. In another four years, very little of this material will be preserved. I have been attempting this year to obtain photographs of some particularly important sites by hiring students or funding friends to make trips, but this has been an expensive and only sometimes successful stop-gap. Someone needs to be working on this now, full time, or many of these beautiful frescoes will be lost forever.

It's also difficult to explain simply the scale of the physical and cultural destruction that's taken place in China over the last sixty years. In the 1940s, surveys north of Beijing showed that every village had between four and ten temple buildings, all with frescoes, statues, inscriptions, etc. Now, 95% of villages have no temples. A god that survives with four or five intact pre-Communist iconographies in rural north China would be considered well-attested, if anyone knew where all those iconographies were located. County-level governments might protect a few larger temple sites, but most village shrines are vulnerable to theft, collapse, or destructive renovation at the whim of the villagers. This is not Italy or France - these things are very rare and getting rarer. They need to be documented now.

My goal is to take a leave of absence from my PhD program, buy a motorcycle and a better camera than I now have, and set out again as a documentarian into the villages of north China. I will re-visit those villages where I feel that my first documentation was not thorough enough. I now have a good working relationship with the county-level cultural bureau in my main research county, so I should be able to get access to those temples which were closed to me earlier. I will then widen my survey to include the whole of China north and west of the Taihang Mountains, including the northern regions of Hebei, Shanxi, and Shaanxi provinces. I have become good at spotting old temples from satellite images (their locations within the village are seldom random), and with time I should be able to visit many or most of the sites where I'm aware village temples still exist.

If you want to understand the material and how this type of work is done, the below links give some idea. One place to look is a short piece I wrote recently titled, "Hannibal's North-Chinese Village Antiquities Search and Rescue Handbook". Although it's meant as a teaching text for my hirees and volunteers, it does explain the process of doing documentary survey work in villages, and what type of results I'm hoping to get. If you want to see documentary galleries of the type I hope to create, you can view the below iconographies of the Ladies 娘娘 , Lord Guan 關公 , the Dragon Kings 龍王 (dated to 1709) , the Mansions of the Western Seas 西洋樓 , or the Images of the Hundred Trades 百工圖 .

Below: Possibly 18th-century fresco depicting Avalokiteśvara/Guanyin 觀音 for which I do not have thorough documentation. In the 1940s, a survey counted 155 Avalokiteśvara iconographies in 212 villages. Those are all gone. I've been to 380 villages in Yu County and I know of three intact front-wall iconographies. The photograph is from 2014. I do not know if the fresco remains there now; the building in any case did not have a door and the roof is streaking mud down onto the painting.

Ultimately, my goal is to create a freely-available online database of north-Chinese village temple frescoes. This database will identify the main iconographic types and tropes and preserve and curate the extant examples for scholarly use. (I've already attempted something like this with the material I now have here, see Part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4 ; this is just an idea of what's out there and the documentary and cataloguing work which needs to be done with it.) This will include both frescoes which are damaged and frescoes which have been conserved by locals or local governments; even when such frescoes are protected in China, they are rarely reproduced in complete form or otherwise made available to scholars. Beyond just preserving images of these beautiful and rapidly vanishing frescoes, this data set could be used to answer a great number of currently open questions - what were the main gods of the north Chinese villages? What were their iconographies? What stories did they tell? When did these gods and iconographies appear? How did pre-modern rural Chinese artistic and religious traditions function? How did they relate to the "high" artistic traditions in China? What were the textual sources of these traditions? How did these village traditions interact with the Western artistic influences that began entering China from the 18th century?

Below: Possibly 17th or 18th century fresco showing the Dragon Kings 龍王 riding out to dispense rain. I have some photographs of this but not complete documentation. The photo was taken in 2014 and the building was heavily damaged structurally at that time; I do not know if the images remain there now.

At the moment, I have roughly 2000 dollars saved up for this purpose, plus a bit more in a Chinese bank account. If I can raise another $8000 to reach an even ten thousand, I will take a leave of absence from Berkeley at the end of that semester and set out with a camera into rural north China until my money runs out. I hope to do this whatever happens with or without money at the end of this year, but if I can reach my goal by the end (or beginning?) of this semester, I will leave earlier. I estimate that 10,000 dollars and a tent will allow me to survive in rural north China for perhaps eight months to a year. Up-front expenses will include: flight tickets (~$1000), a new camera (~$700) and a motorcycle (~$1000). Progressive expenses will include petrol costs, food costs, and accommodation costs when in the cities. Until I reach $10,000, I will continue to spend money on sponsoring trips to the region by friends and volunteers based in Beijing, and to sponsor my own trips during winter and summer breaks from Berkeley.

Any donation you make will ultimately get used. Even if I do not reach the goal of 10,000, I will fund a later, slower survey by working and making money from a day job. The more I get now though, the faster I can get out into the field, and the more material can be saved from theft and collapse. I will continue to put information about how this money is being used here, on my blog, and eventually on an email list if I get enough interested donors.

I believe this preservation work is important, and that anybody who cares about art or history should also think it's important. I also believe that it needs to be done now - not next year, definitely not in five years. I thank you all for your support - please forward to friends and family, anyone who has an interest in China, art, or preservation!

- Hannibal C. Taubes

Below: Two walls of an opera stage, depicting the Jesuit-built palaces outside of Beijing, and a scene from a early 19th century popular novel. One wall is only two-thirds intact, and the collapse of part of the side of the roof has spilled mud down over most of the other wall. These frescoes were still there when I visited in July 2016, but since the stage is now kept open, it's impossible to say for how long.

Below: A shrine room dedicated to the Yama Kings 閻王, the Buddhist afterlife judges, photographed for the first time by me in July 2017. Thieves have gridded out the heavily damaged 19th century fresco for removal, apparently without success:

Organizer

Hannibal Taubes

Organizer

Belmont, MA