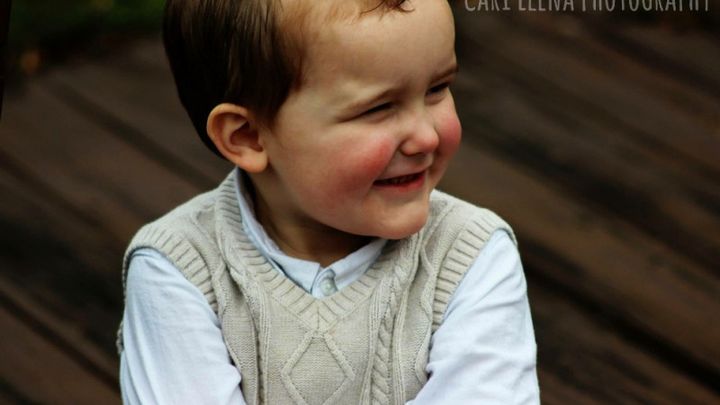

Noah's Medical Miracle

Donation protected

Three days ago I had a disagreement with my 6 year old son, Noah.

His older brother, a healthy, empathetic, and kind boy, was at his after-school running program and Noah and I were enjoying an hour of Mommy/Son time. Often times during this hour I encourage outside play but the weather didn't permit. Instead he opted to enjoy some time at home and after playing and chatting about some of his favorite subjects (superheros, Legos, and the newest puppy picture he hung next to his bed) it was time to get into the car. He complained about having to leave the fun while I encouraged him to invite his brother to play when he got home. Then, to change the subject, I asked if he'd like to be in running club someday. All of a sudden those words I hated to hear were uttered.

"Mom. I can't."

Naturally, as I'm sure most of you would do, I argued.

"Baby, that's ridiculous. Of course you can. You just need to work at it." To which his simple response was pointing to his head and holding up his hands. It was a painful revelation looking at that matter-of-fact expression. What could I say? How much do I encourage working toward a dream when in so many ways- he was right?

My son has a clinical diagnosis of Landau Kleffner's Syndrome (LKS) which is an extremely rare variation of childhood epilepsy.

Those of you familiar with epilepsy know that seizures can strike at any time. A sudden disturbance in the brain that can affect his entire life. While it is easier to deal with epilepsy when you know what your triggers are, Noah has no known triggers. As a result his life is a measure of vital balance. He can't be overheated, dehydrated, sleepless, sick, stressed out, too cold or malnourished without running an increased risk of a seizure that will paralyze him for hours and set him back mentally for days. He was right, he can't join running club. He can't ride the skateboard he's been begging for in the past year. He can't take swimming lessons or even be without a trained caretaker in any capacity. At least not until his seizures can be medically controlled. To make matters worse, within the past 6 months he has developed a debilitating tremor in his arms and hands that is pronounced when his seizure activity is worse or when any of the previously mentioned categories are off balance. When he held up his shaking hands for me in the car, he couldn't hold them still, let alone feed himself, dress himself, or even wipe after using the bathroom at times in the morning.

While I won't pretend to be a math expert, after simple calculations, along with this diagnosis came an interesting set of statistics.

Childhood epilepsy affects roughly 300,000 children under the age of 14.

1 in 10,000 of these children are affected by LKS.

Since the discovery of LKS in 1957, approximately 4 children are diagnosed per year.

The physical struggles aside, the most notable effect of LKS is called verbal aphasia. Aphasia is the loss of ability to understand or express speech due to brain damage. In children with this disease there are two red flags. The first and often more obvious is the extreme challenges in communication. As Noah missed every milestone in infancy, then failed to be able to discern different sounds, we began pushing for testing. At two years old he began speech and occupational therapies and letters like SPD (sensory processing disorder) and CAPD (central auditory processing disorder) were thrown around. It wasn't until he was 3 that his seizures began in a violent way. Because he had struggled with communication for so long, it wasn't included in diagnosing why these seizures were happening. We cycled through many medications, adjusting diets, and giving up dreams of homeschooling in lieu of special needs programs in the public school system. At 5 years old we had established a fantastic team of educators and doctors to give him the best care available. As his mother, even still I had trouble adjusting my expectations of what his future would hold. I spent countless sleepless nights pouring over medical journals and research over epilepsy in general and tried to find some kind of answer that fit my son's symptoms. It wasn't until April of 2017 that things really changed.

Once again, as seemed to happen several times in a year, his behavior and abilities began to decline. Often times I would berate myself for being too harsh. Perhaps I was reading into details that didn't matter? Perhaps this is just the way my son would learn? Perhaps I was comparing him too much to his brother? But all the same, I noted the changes in his ability to move and what seemed like an endless stream of sleepless nights and seizures. The second his kindergarten teacher contacted me and expressed concern over him losing his ability to write his name, a skill he had practiced for years in therapy, I knew I wasn't imagining things. I put together a list of evidence (including pictures of his name before and after the changes) for his medical team, and they agreed that something wasn't right. Then we discovered red flag number two.

ESES (essentially actively seizing during slow wave sleep) is extremely uncommon for epileptics. Generally the most vulnerable point of sleeping for epileptics is as they're falling asleep. Have you ever been falling asleep and suddenly were jolted awake by your body? While not necessarily related, it's easy to identify with. For Noah, his seizure spikes never seemed to shut off. This meant when his body should be resting and recharging, he was never able to. A vicious cycle when you consider that sleep is a vital part of a balance he desperately needs.

At first this diagnosis was a strange and bitter blessing. With a diagnosis comes a direction and list of methods to explore for treatment. Noah was desperately behind and struggling constantly. This became his normal. If we could only discover the combination of interventions that would allow him to go without seizures, then he could FINALLY make the progress that would allow him to be a functioning member of society. But if there's one thing I've realized in his short life, it's that he seems to have won the medical jackpot.

There are different ways to treat LKS that have various degrees of success and we systematically checked them off for the duration of this year. His medical team monitored his brain activity and we kept careful notes about his physical and mental decline. We poured every resource we had into finding answers, EEGs, genetic testing, sometimes 7-12 medications at a time. Anything to give our son relief. Unfortunately there are people who suffer from LKS who don't respond to intervention- and so far Noah is one of them. Four EEG's (brainwave monitoring), two steriod treatments, and 3 adjustments to medications later his condition has only worsened.

As the year is coming to a close, we have finally received the phone call we dreaded. One of the many phone calls I didn't know could exist until it happened. Our medical team, associated with one of the best hospitals in the state, no longer had the resources to help him. We have done everything we can to no avail and need bigger players to step in and look closer. We know that the longer this condition continues without successful intervention, the more likely he will have debilitating communication and mental deficits into adulthood. Those dreams of him enjoying a full life with his peers, of graduating college, or starting a family, begin to melt away before our eyes. It's impossible not to ask "why him?"

We have now been directed to a small list of national institutions with greater resources that could help him. People with extensive and specific pediatric epilepsy training and the ability to look at his body with more precision than I thought possible. People we would rely on to develop a new plan of treatment. As we discussed what this means, suddenly the realities of hospitalizations, IVIG or IV steroid treatments sink in.There have even been suggestions that he is now a good candidate for brain surgery.

And yet here I am still wondering if I'm imagining things. Still wondering if this is really happening.

This brings me to why we came here. We humans are naturally prideful creatures. There is a measure of embarrassment to me that I no longer have the resources to give my son what he desperately needs. This year we find ourselves significantly in debt simply to finding answers that never came. Now that we are being pointed in a new direction, it bothers me that I don't know how or even if we can give him everything he needs. These new treatment options are far more expensive than what we have done thus far. Far more dangerous. While humbling myself is hard for me, we would do anything for our son.

To those who have sacrificed the time it took to listen to me, thank you. Even knowing our story is one step in the right direction.

My family needs help. Any donation is greatly appreciated, and if you find you're unable, please share this with someone you know. Please extend what prayers you can. I dream of the man my son will someday be able to be and with your help, he will have the opportunity.

For those who wish to learn more about this rare disease, please explore the following links:

Basics about Laundau Kleffner's Syndrome

Explanation of ESES

Explanation of IVIG

Brief Explanation of Brain Surgery

Organizer

Rachel Roach

Organizer

Stillwater, OK