Acee's Summer Ballet Experience

Donation protected

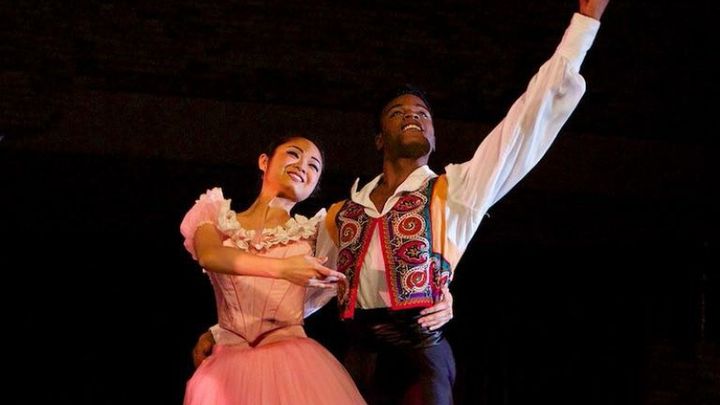

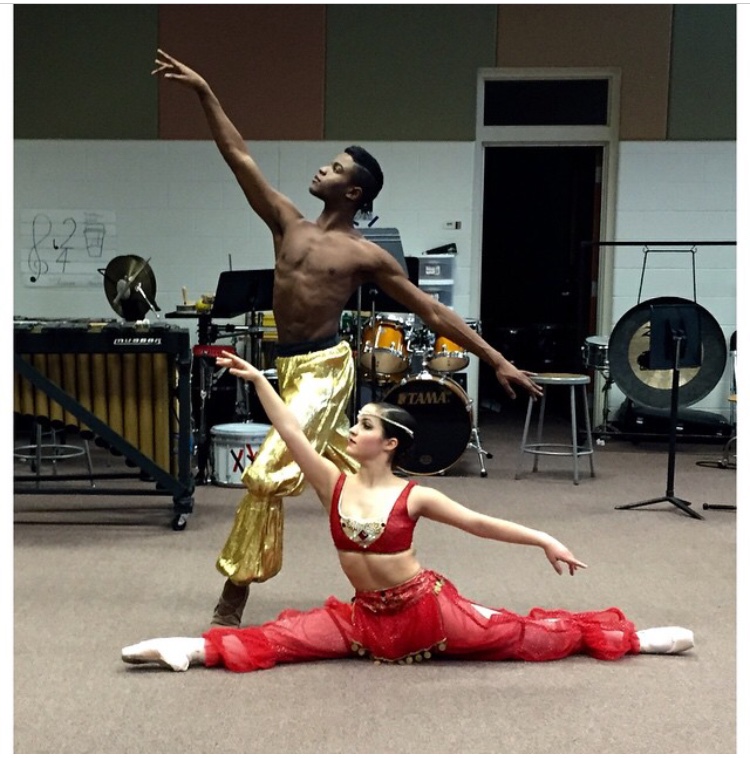

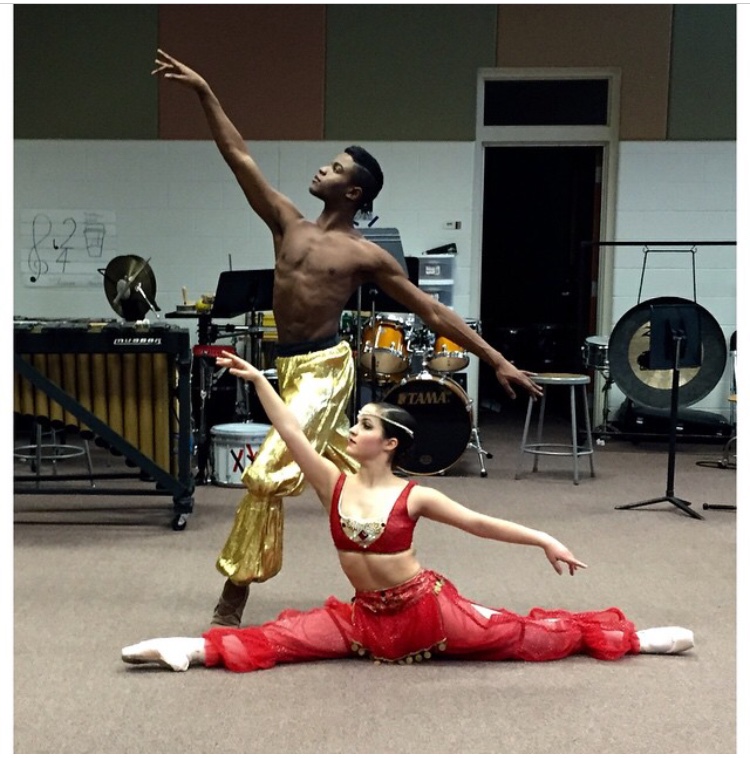

Summer 2014 Nutcracker 2014

Nutcracker 2014 Father & Son 2014

Father & Son 2014

This is my son, Acee. His dream is to be a professional ballet dancer and we have learned one thing for sure, "Opportunity costs money." Acee is currently a full time member of the Milwaukee Ballet Second Company (MBII). He dances sometimes 12 hours a day, five to seven days a week, but this is a non-paid position. I am a public school teacher and I do my best to provide for us. Last Sunday, Acee auditioned for the summer program at Hubbard Street Dance Company in Chicago. 650 dancers auditioned and Acee was accepted into the program but the cost is $2000. A program such as this would be an amazing experience for him and help him to eventually garner a full time paid position with a professional company. I don't want Acee to miss out on this opportunity and we need help from the community to make it possible. My son has an amazing story but instead of attempting to tell our story, I will let you read a recent article about us from the Journal/Sentinel this past December:

"The invitation was from a boy named Acee, about 12 at the time, to the teacher helping him learn how to read.

"You know you could be my dad."

It was not the first time Allan Laird, then a 39-year-old teacher in the Milwaukee Public Schools, had encountered children who desperately needed love. And comfort. And hope.

But Acee was serious. His life had been a series of 14 foster homes by the time he met Laird a little more than a decade ago at Sherman Multicultural Arts School. His earliest memory was his mother murdering his aunt in front of him when he was just 2.

After administering a reading assessment to the boy that summer, Laird, a special-education teacher, realized Acee was far, far behind. He started working with the boy on literacy exercises that summer and into the school year.

In the fall of 2003, Acee showed up to school with bruises.

Laird called Child Protective Services.

"I asked you before if you would be my dad," Acee told him. "You need to be my dad."

Laird was single. No children.

•••

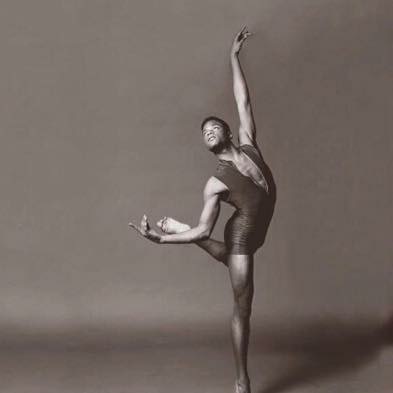

It's a recent Friday evening in a windowless south side dance studio.

Young adults twist, spin and stretch, manipulate their limbs and those of others, like painters choosing brushes.

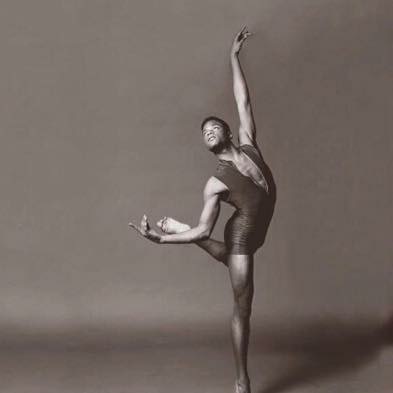

Acee — pronounced just like the letters "A.C." — is now 5-feet-10 and 23 years old. The dancers are working on the next show. Acee responds to the choreographer's instructions, lifting his partner, turning her away, trying several leaps that are supposed to make him look like he has superhero powers. Not all of them work. Some are awkward.

He continues to try for something better.

It's all he's ever done.

•••

Allan Laird got in touch with a social worker about becoming a foster parent. He enrolled in a fast track for training.

He wasn't prepared for resistance from Child Protective Services. Reunification with the biological family was still a priority for the bureau.

And Laird's intentions were called into question — a single man wanting to adopt a boy. Parents of his other students and his principal vouched for his character. His family rose to his defense.

The bureaucratic battles stretched for months.

The court appearances were intense, especially when Acee testified on the stand against his mother.

It was Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Jane Carroll, then a judge in Children's Court, who issued the decision approving Laird as Acee's foster father in February 2005.

This young man has had to listen to adults and do whatever they said for his entire life, and it has never been successful for him, Laird remembers Carroll saying.

"For once in his life, I want to listen to him."

•••

Laird tried to give Acee an outlet for his energy. A hip-hop class. Then ballet.

He was 15 in the summer of 2007, in a floppy T-shirt and basketball shorts, dancing at barre next to girls in pink leotards and tutus.

And he loved it.

"It was challenging," he remembers. "You had to do exactly what the teacher said. It taught me structure and patience and how to keep trying for perfection."

•••

When Acee moved into Laird's house on Milwaukee's east side in 2005, some adaptations were easy. The only kind of Christmas Acee had known was one where his mom gave him a dollar or two to buy a candy bar at the corner store. Now there was a huge dinner, extended family who enveloped him, presents from Santa on Christmas morning — a tradition Laird continues to this day.

But there were challenges. Acee still got into fights at school. He rebelled against Laird's rules about what friends he could hang with, and when he could be out. He had to do homework.

During a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee program for teens in the summer of 2006, Acee acted out so much that Laird was asked to remove his son from the program.

Laird insisted on better behavior. He drilled Acee in reading and math and writing, to speed up his academic progress. He had a binder full of words to learn, with quizzes at the end of the week — not in school, but at home.

Laird even read aloud passages from Ruby Payne's book, "A Framework for Understanding Poverty," so Acee could better understand his background.

"If he wanted to step up from poverty to middle class, he had to understand the forces that were going to try to pull him back," Laird said.

By the time Acee attended St. Thomas More High School, his favorite book from English class was "The Great Gatsby," because he identified with the lead character. He spent hours getting help from his father for a critical essay about the book.

When Acee took the ACT exam, his writing score was in the 96th percentile.

•••

Spring 2012.

Acee had accelerated through the Milwaukee Ballet School and Academy.

But he had just found out he would not be admitted to Milwaukee Ballet II, the apprenticeship program for aspiring professional dancers.

Rolando Yanes, Milwaukee Ballet School and Milwaukee Ballet II director, said Acee wasn't physically or mentally ready to advance.

At that point, most dancers give up. They go to school, pursue different careers, get jobs.

For two years, Acee took courses at UWM, and worked retail and restaurant jobs. He auditioned for a modern dance performance at the university. As he started to move on stage again, he realized he wanted to dance professionally.

In January, he tried out again for the Milwaukee Ballet's intensive summer institute, and was accepted.

His body was more developed. So was his mind. He was stronger and more focused.

After the sixth week of the institute — the audition week — all the dancers making bids for the ballet's second company got sealed letters.

Acee stepped outside and into the alley to read his letter.

When Laird got the call, his son cried so hard, he was unclear.

Finally, four words emerged.

"Dad, I got in."

Getting into the ballet's second company was the proudest day of his life, he said.

"I didn't grow up knowing what it meant to work," he said. "Or how to get to the highest level of something, or what it means to feel accomplished."

What's next?

First, Acee Day. That's the anniversary of his adoption by Laird, which became official on Jan. 3, 2008.

And January and February is when the dancers in the second company audition for jobs in other cities. Most will not be offered a job in the Milwaukee Ballet.

Acee hopes he'll get offered a contract to stay in Milwaukee. But he has January auditions lined up at various dance companies in Chicago.

Wherever his career takes him now, he's not afraid.

"I've grown eagle's wings," he said. "I can fly."

I hope you can help Acee reach his dreams.

Nutcracker 2014

Nutcracker 2014 Father & Son 2014

Father & Son 2014

This is my son, Acee. His dream is to be a professional ballet dancer and we have learned one thing for sure, "Opportunity costs money." Acee is currently a full time member of the Milwaukee Ballet Second Company (MBII). He dances sometimes 12 hours a day, five to seven days a week, but this is a non-paid position. I am a public school teacher and I do my best to provide for us. Last Sunday, Acee auditioned for the summer program at Hubbard Street Dance Company in Chicago. 650 dancers auditioned and Acee was accepted into the program but the cost is $2000. A program such as this would be an amazing experience for him and help him to eventually garner a full time paid position with a professional company. I don't want Acee to miss out on this opportunity and we need help from the community to make it possible. My son has an amazing story but instead of attempting to tell our story, I will let you read a recent article about us from the Journal/Sentinel this past December:

"The invitation was from a boy named Acee, about 12 at the time, to the teacher helping him learn how to read.

"You know you could be my dad."

It was not the first time Allan Laird, then a 39-year-old teacher in the Milwaukee Public Schools, had encountered children who desperately needed love. And comfort. And hope.

But Acee was serious. His life had been a series of 14 foster homes by the time he met Laird a little more than a decade ago at Sherman Multicultural Arts School. His earliest memory was his mother murdering his aunt in front of him when he was just 2.

After administering a reading assessment to the boy that summer, Laird, a special-education teacher, realized Acee was far, far behind. He started working with the boy on literacy exercises that summer and into the school year.

In the fall of 2003, Acee showed up to school with bruises.

Laird called Child Protective Services.

"I asked you before if you would be my dad," Acee told him. "You need to be my dad."

Laird was single. No children.

•••

It's a recent Friday evening in a windowless south side dance studio.

Young adults twist, spin and stretch, manipulate their limbs and those of others, like painters choosing brushes.

Acee — pronounced just like the letters "A.C." — is now 5-feet-10 and 23 years old. The dancers are working on the next show. Acee responds to the choreographer's instructions, lifting his partner, turning her away, trying several leaps that are supposed to make him look like he has superhero powers. Not all of them work. Some are awkward.

He continues to try for something better.

It's all he's ever done.

•••

Allan Laird got in touch with a social worker about becoming a foster parent. He enrolled in a fast track for training.

He wasn't prepared for resistance from Child Protective Services. Reunification with the biological family was still a priority for the bureau.

And Laird's intentions were called into question — a single man wanting to adopt a boy. Parents of his other students and his principal vouched for his character. His family rose to his defense.

The bureaucratic battles stretched for months.

The court appearances were intense, especially when Acee testified on the stand against his mother.

It was Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Jane Carroll, then a judge in Children's Court, who issued the decision approving Laird as Acee's foster father in February 2005.

This young man has had to listen to adults and do whatever they said for his entire life, and it has never been successful for him, Laird remembers Carroll saying.

"For once in his life, I want to listen to him."

•••

Laird tried to give Acee an outlet for his energy. A hip-hop class. Then ballet.

He was 15 in the summer of 2007, in a floppy T-shirt and basketball shorts, dancing at barre next to girls in pink leotards and tutus.

And he loved it.

"It was challenging," he remembers. "You had to do exactly what the teacher said. It taught me structure and patience and how to keep trying for perfection."

•••

When Acee moved into Laird's house on Milwaukee's east side in 2005, some adaptations were easy. The only kind of Christmas Acee had known was one where his mom gave him a dollar or two to buy a candy bar at the corner store. Now there was a huge dinner, extended family who enveloped him, presents from Santa on Christmas morning — a tradition Laird continues to this day.

But there were challenges. Acee still got into fights at school. He rebelled against Laird's rules about what friends he could hang with, and when he could be out. He had to do homework.

During a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee program for teens in the summer of 2006, Acee acted out so much that Laird was asked to remove his son from the program.

Laird insisted on better behavior. He drilled Acee in reading and math and writing, to speed up his academic progress. He had a binder full of words to learn, with quizzes at the end of the week — not in school, but at home.

Laird even read aloud passages from Ruby Payne's book, "A Framework for Understanding Poverty," so Acee could better understand his background.

"If he wanted to step up from poverty to middle class, he had to understand the forces that were going to try to pull him back," Laird said.

By the time Acee attended St. Thomas More High School, his favorite book from English class was "The Great Gatsby," because he identified with the lead character. He spent hours getting help from his father for a critical essay about the book.

When Acee took the ACT exam, his writing score was in the 96th percentile.

•••

Spring 2012.

Acee had accelerated through the Milwaukee Ballet School and Academy.

But he had just found out he would not be admitted to Milwaukee Ballet II, the apprenticeship program for aspiring professional dancers.

Rolando Yanes, Milwaukee Ballet School and Milwaukee Ballet II director, said Acee wasn't physically or mentally ready to advance.

At that point, most dancers give up. They go to school, pursue different careers, get jobs.

For two years, Acee took courses at UWM, and worked retail and restaurant jobs. He auditioned for a modern dance performance at the university. As he started to move on stage again, he realized he wanted to dance professionally.

In January, he tried out again for the Milwaukee Ballet's intensive summer institute, and was accepted.

His body was more developed. So was his mind. He was stronger and more focused.

After the sixth week of the institute — the audition week — all the dancers making bids for the ballet's second company got sealed letters.

Acee stepped outside and into the alley to read his letter.

When Laird got the call, his son cried so hard, he was unclear.

Finally, four words emerged.

"Dad, I got in."

Getting into the ballet's second company was the proudest day of his life, he said.

"I didn't grow up knowing what it meant to work," he said. "Or how to get to the highest level of something, or what it means to feel accomplished."

What's next?

First, Acee Day. That's the anniversary of his adoption by Laird, which became official on Jan. 3, 2008.

And January and February is when the dancers in the second company audition for jobs in other cities. Most will not be offered a job in the Milwaukee Ballet.

Acee hopes he'll get offered a contract to stay in Milwaukee. But he has January auditions lined up at various dance companies in Chicago.

Wherever his career takes him now, he's not afraid.

"I've grown eagle's wings," he said. "I can fly."

I hope you can help Acee reach his dreams.

Organizer

Allan Laird

Organizer

Milwaukee, WI